Growing up in Queens, Uri Cohen had Bukharian Jews as his neighbors but like many Ashkenazim, he did not know about their culture, history and minhagim. When he became the Executive Director of Queens College Hillel seven years ago, he noticed that the largest group of likely Hillel participants was not feeling represented. “There are 4,000 Jewish students on campus and 24 percent of them are Bukharian,” said Cohen. “The volume of the Bukharian voice here has the potential to be very loud. We are taking this opportunity very seriously.”

At the time of his arrival on campus, many Bukharian students did not have a venue to express their unique Jewish identity. When Cohen sought out their concerns, he heard their fears of being the last generation to know of their history and culture as they either assimilated into the larger Jewish population, or into the overall melting pot of intermarriage.

On my own Touro College campus, I am happy to see Bukharian students with kippot, skirts, and a strong sense of Torah observance. But when my students submit reports on great rabbis or events in Jewish history, the topics often relate to Ashkenazim. They do not know about the gedolim of their own community, and events that shaped the course of Bukharian Jewish history. They have forgotten about shashmaqam music, and foods such as samsa and bakhsh, or why the joma robe is worn at festive occasions? I am happy that my students are observant and know the narrative of the Torah, but what about the centuries between the time of Tanakh and today?

Over the years, there have been efforts to keep Bukharian Jewish students at Queens College engaged with their roots, most notably with Imanuel Rybakov’s first-of-its-kind class on Bukharian Jews, but the fear was that once the initiator moves on, on the program would close. With the arrival of Manashe Khaimov as Hillel’s Director of Community Engagement and Development, the effort appears more organized and sustained.

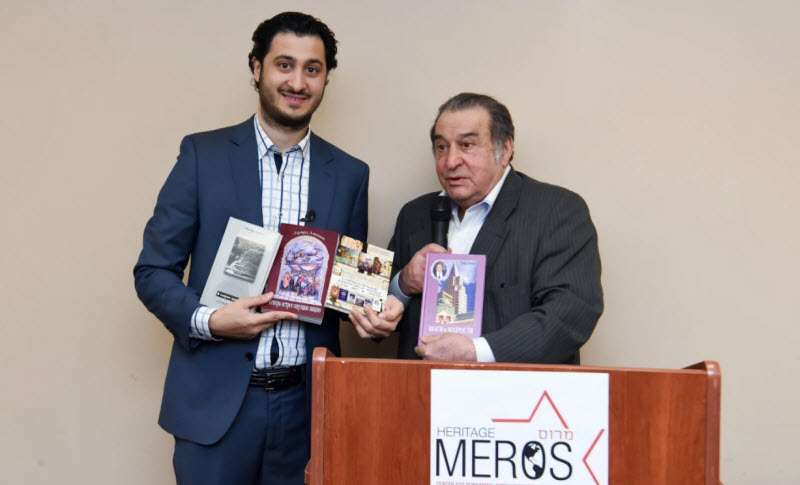

On March 6, Khaimov dedicated the Meros Center for Bukharian Jewish Research & Identity at the Queens College Hillel, a place for students to learn about their culture through literature, music, food, and lectures. The event was kicked off by a three-piece shashamaqam ensemble and greetings by senior cultural figures in the community. The center functions in partnership with Hillel and the Orthodox Union’s Jewish Learning Initiative on Campus (JLIC) which provides religious programming on college campuses.

In his interactions with Bukharian Jews on campus, Khaimov identified three types: those who are proud and seeking religious growth; those who are proud of their identity but not interested in religion; and those who seek to distance themselves from their Bukharian and Jewish identities. “All students are challenged when they come to college. Bukharian students tend to hide their identity. Some say that they’re Russian. This leads to low self-esteem,” said Khaimov. “It’s about being confident in yourself. If a person knows where he comes from, he is more confident in himself.”

As Khaimov sees it, religious outreach organizations such as Chazaq and Emet are doing great work in promoting religious observance, but with little attention given to the cultural aspects of Bukharian Jewry. “I’ve heard from yeshivas where Bukharian girls feel second class and have trouble explaining who they really are,” said Khaimov.

At Meros, which translates as heritage in Bukhori, students have access to a bookshelf of materials in English about Bukharian Jews. Each week, a Chaikhona gathering brings Bukharian food and music to a learning session that covers culture, history, and religion. Internships connect students to Jewish nonprofits and cultural institutions, and trips are provided to the Bukharian Jewish Museum operated within the Jewish Institute of Queens.

Cohen sees Meros as an opportunity to bring Bukharian students into the Hillel tent, while enhancing the reputation of Queens College. Every university has a center focusing on a particular ethnic or religious group. With the largest Bukharian student body in the country, Queens College has become the ideal place for the public to learn about their culture, and for Bukharian Jews to better understand themselves.

In his long-term vision for Bukharian Jews in America, Khaimov regards his Syrian Jewish neighbors in Brooklyn as an ideal example. “Syrians are connected to their culture and the larger world. They’re tribal and universal.”

By SERGEY KADINSKY