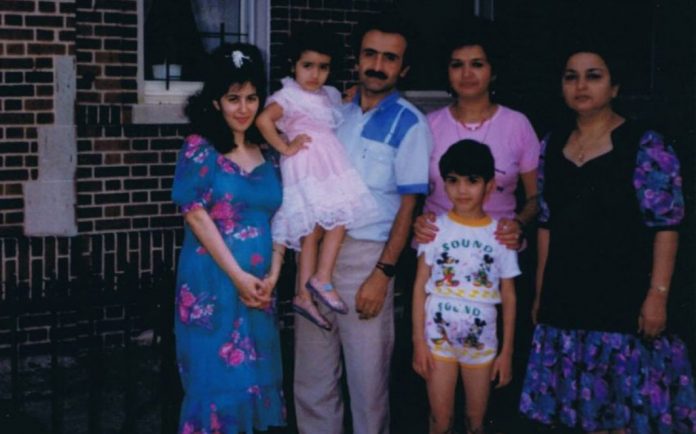

Nelly Iskhakova was unaware of the struggles that awaited her after she immigrated from Uzbekistan to America.

Excitement filled Nelly Iskhakova when she and 30 of her family members boarded a plane in 1991 to travel from Uzbekistan to America. But she didn’t know the journey that awaited her.

After Iskhakova’s relative brought news that the family could leave the country as refugees, she and her husband were in shock.

“We were in disbelief and thought, ‘That’s not true,’ since most people who left in the mid-80s were persecuted or considered traitors,” she said.

Two years earlier, Iskhakova’s relatives traveled to Moscow to obtain immigration forms. They were told to await an interview and explain that they sought to leave Uzbekistan because of religious persecution.

Months later, Iskhakova and her husband were summoned for an immigration interview in Moscow. “We really didn’t think much of it, but when we heard the news, we began to think this is really happening and were so excited,” Iskhakova said.

Life in Uzbekistan for her family was a challenge, including the practice of Judaism. As a child, Iskhakova said, she was the only Jew at her school of 2,000 students. Her teacher kept a journal that disclosed students’ religions.

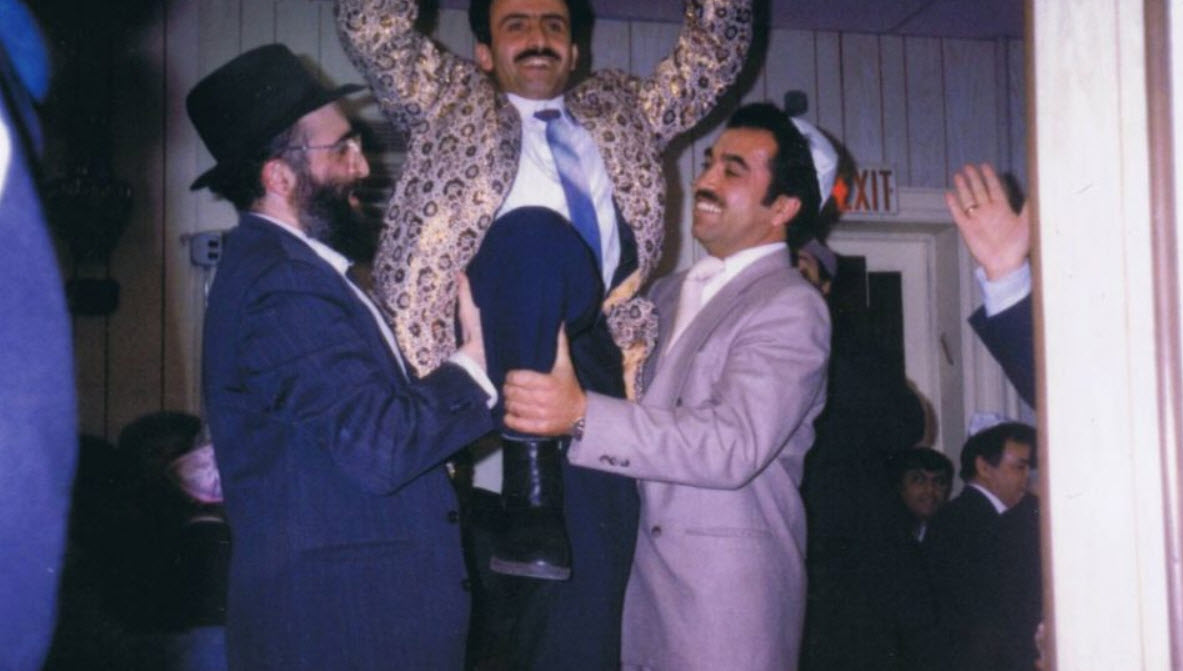

When it was time for her brother to celebrate becoming a bar mitzvah, Iskhakova said the preparations were done in secret.

“My family didn’t want to attract the government attention, since having religious beliefs was forbidden in the country,” she said. In addition to observing the High Holidays, the family kept Shabbat and traveled to a special market to purchase kosher meat every Passover.

Over time living conditions in Uzbekistan deteriorated. “You couldn’t even buy bread,” Iskhakova said.

She thinks her husband’s Judaism kept him from getting a managerial position. “We got to a point where we began to think, ‘OK, where do we go from here? What direction is the country headed?’” she said. “We didn’t see a future for our kids but still wanted to practice our religious beliefs.”

In a final attempt to leave Uzbekistan, Iskhakova and her husband began selling everything they had to raise money for their departure. “The process was so difficult for us up that point,” she said. “We were trying to sell our house but were not supposed to tell our neighbors why, and because people knew a mass of Jews was leaving, everyone was selling their house for basically nothing.”

When the family arrived in New York, excitement turned into disappointment. “We didn’t know what to expect and realized that the city was very dirty,” Iskhakova said. “It was a culture shock.”

Daily life began to improve when the government provided her daughter free day care and English classes through the Hebrew Immigration Aid Society. She later received financial aid and applied to and graduated from a nursing school.

“We tried to take advantage of everything, and it was very helpful,” she said.

But life in New York wasn’t always friendly. One time Iskhakova’s daughter suffered an injury, and ultra-Orthodox medics arrived to provide aid. But when they discovered Iskhakova was Bukharian, they appeared uncaring.

“We didn’t know any English. … All I remember is that when a translator came to tell the medics we were Jewish, they said, ‘No, they’re not Jewish. They’re not Jewish,’” Iskhakova said. “It was very hurtful.”

After five years in New York, Iskhakova and her husband decided to move to Atlanta. Her relatives helped them settle here, so they did not need assistance from the Jewish community. Iskhakova added that they felt humiliated by New York’s welfare offices and did not wish to experience the same treatment in Georgia.

Iskhakova is a member of Congregation Beit Yitzchak and believes that Atlanta has become more welcoming since the early ’90s. “When we go to Chabad here in Atlanta, people are very pleasant and welcoming, but I think it is because more people have immigrated to Atlanta and the community has a better understanding of who we are,” she said. “Before, we were just a part of the Orthodox community and people didn’t know who we were, but over the years people have come to understand and are more receptive.”

credit to atlantajewishtimes