QUEENS — On Valentine’s Day this year, Lidiya Isakbaev called her son, Boris, to make sure he was OK.

The 28-year-old, who was staying with a neighbor that day, had struggled with opioid addiction for the past eight years and his mother often worried about him.

A little after 10 p.m., her son texted her back saying he’d be home in 20 minutes — but he never showed up.

The neighbor, who had been trying to help Boris overcome his habit, called Isakbaev to tell her that her son had taken pills “and was not even able to stand up straight,” his mother recalled.

So she ran to the neighbor’s apartment, where she found Boris “just sleeping,” said Isakbaev, 49, a registered nurse. When she returned to check on him the next morning, “he was still sleeping, but he was breathing with difficulty.”

They called 911, but when paramedics arrived, it was too late, she said.

“He left us,” she remembered of that day, her eyes filling with tears.

The cause of Boris’s death was an overdose of fentanyl and morphine mixed with Xanax, according to the city Medical Examiner’s office.

With the opioid epidemic ravaging communities throughout the city and country, it has also claimed numerous victims in the tight-knit Bukharian Jewish community of Central Queens.

Like the Isakbaevs, tens of thousands of Bukharian Jews who immigrated to the United States primarily from Tajikistan and Uzbekistan settled mainly in Forest Hills, Rego Park and Briarwood.

This year alone, there were at least nine overdoses in the community — twice as many as last year — according to a local rabbi with first-hand knowledge of the situation.

The rabbi spoke on the condition of anonymity because he didn’t want to be seen as betraying the community’s secrets. He said the issue is sensitive and that “people don’t want to embarrass the family” by revealing the cause of death.

Advocates fear the numbers may be even higher because of the stigma that comes with drug addiction in the Bukharian Jewish community.

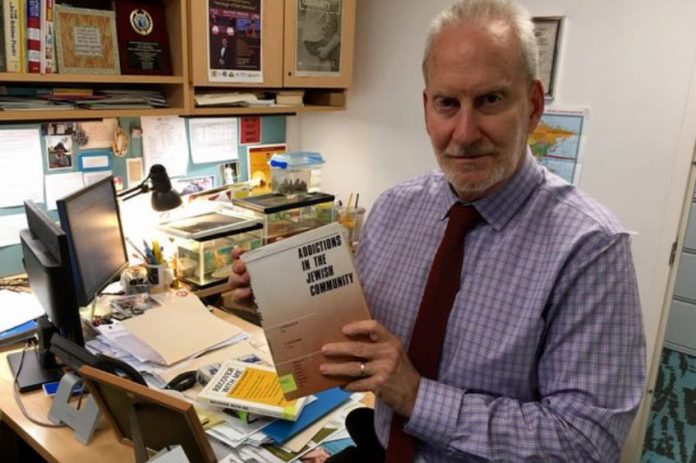

“Death can be attributed to cardiac arrest, or families can say they died in the sleep, or that it’s unexplained or they must have had a blood clot,” explained Jonathan Katz, director of Jewish Community Services at the Jewish Board, a nonprofit providing social and mental-health services.

“And these things can all be true, but they are the result of the opioid use rather than only cause of death,” Katz added.

Since Jewish tradition requires burials to take place within 24 hours, autopsies are usually not performed in cases that do not involve the police, he added.

Katz noted that he has begun to see “more opioid abuse in the Jewish community in general over the past three to four years.”

“I think that it’s a combination of a variety of factors,” he said, citing things like doctors and drug companies promoting different types of opioids more aggressively over the past several years, as well economic and housing issues affecting many families in New York.

In the case of the Bukharian Jewish community, cultural conflicts also play a role, Katz said.

“To have to leave your home country and come to a new land, a new society, can be very challenging,” he explained “There are also stress factors like [parents] wanting their children to have certain culture and values… and for the young people it’s a stress factor, too, because their parents are saying to them: ‘We want you to hold on to our values, our culture and our behaviors,’ and the young people feel oftentimes very pressured by that.”

Bukharian Jews began moving to the area in the 1960s, but the majority arrived after the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s.

Today, approximately 60,000 Bukharian Jews lives in Central Queens, according to the Bukharian Jewish Union (BJU), which serves as a professional and social hub for young members of the community.

The group, alarmed by the recent spike in the number of overdoses, organized a substance abuse awareness forum for families affected by the issue scheduled for Tuesday.

“From my observations, it’s both men and women, poor and rich, kids from public schools and yeshivas,” said BJU’s Manashe Khaimov. “It’s really just an epidemic that folds into any social class.”

Last year, drug overdose deaths hit a record high in the city, killing 1,374 people — including 235 in Queens. That’s up from 937 citywide in 2015, according to the most recent data provided by the city’s Department of Health.

Opioids — which include prescription painkillers such as OxyContin, Vicodin and Percocet, as well as morphine and heroin — were involved in 82 percent of overdose deaths last year, the agency said.

Some in the Bukharian Jewish community said that drug use in its ranks is nothing new, but the stronger synthetic cocktail that has gained popularity over the last few years has brought a new gravity to casual use.

Aron M., 40, who did not want his last name used, said that the Bukharian Jewish community has been dealing with drug addiction for awhile.

He and a group of friends began experimenting with drugs more than two decades ago, when they were in high school, initially just smoking marijuana.

Then some in the group, including his cousin, who dropped out of high school to work as a barber, began shooting heroin.

Aron’s cousin, who he said at one point was using as much as $500 worth of heroin a day, died of an overdose about seven months ago the age of 38.

He added that of his group of about 15 high school friends who began using drugs years ago, five passed away over the past decade due to overdoses. They had all been shooting heroin, he said.

“But in the past, those that passed away from overdoses were not experienced, they didn’t know what was the dosage and they took more than they were supposed to,” Aron said.

“Now, people are dying because [drug dealers] put fentanyl in it,” he added. “It’s not just the dosage, it’s a poison. The drug is too strong, it’s deadly.”

Over the past three years, a rapid increase in the use of fentanyl — a cheaper synthetic opioid that is 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine — has been associated with the rise in overdose deaths. It is commonly mixed with other drugs, oftentimes without users even aware of it.

Last year, fentanyl was involved in 44 percent of all overdose deaths in the city, the Department of Health said.

The Isakbaevs, who came to the U.S. from Uzbekistan in 1993, when Boris was 5, said that they don’t know why he started taking opioids.

“Sometimes you think you have a perfect family — your kids are educated, you are successful, both parents are working, you do everything for the kids the way it’s supposed to be,” his mother said.

Boris once told her that “he felt good after taking these pills and couldn’t live without them,” she added.

Before he started using, he was a straight-A student with a gift for writing and dreams of becoming a doctor, his parents said.

He was accepted to LIU Brooklyn but never attended, later trying twice to take classes at York College, his mother said. But was never able to complete a semester.

“His mind was occupied with it constantly,” his mother said about his habit. “That’s why he couldn’t do anything else.”

Initially, Boris’s parents tried to be strict with their son, taking him for treatment twice. But each time he relapsed almost right away, they said.

To pay for drugs, he began stealing jewelry from their home. Later, they just started giving him money.

“[Addicts] need money all the time,” said his father, Ariel Isakbaev, 52. “I gave him a lot, because I didn’t want somebody to kill him or beat him for that.”

If they could turn back the clock, his parents said they would have sent Boris to another part of the country and never let him come back — because once addicts return to their old environment, “they begin using again,” his father said.

The Isakbaevs, who also have two daughters, said they are trying to learn “to live without him.”

“He taught us to be different with people we are close to,” his father said. “The big problem of all parents is an ego inside us — but all we have to do is to learn to hear our kids.”

credit to dnainfo.com