When the ancient Israelites were slaves in Egypt, they assimilated into Egyptian society – with three key exceptions. They never lost their distinctive Jewish mode of dress, they maintained their Jewish names, and they kept their Jewish language. These three features enabled them to just barely hold on to their Jewish identity.

Scattered far and wide, Jewish communities have carved out distinctive languages, keeping them somewhat apart from the larger non-Jewish communities surrounding them. Dr. Mary Connertey, Teaching Professor Emeritus at Penn State Behrend, explained to Aish.com that “Anywhere we (Jews) have lived we created our own language.”

Sometimes these “Jewish” languages are very similar to the dominant language around them, yet Jewish forms of languages contain clearly distinct elements. Hebrew words, quotes from Jewish prayers and elements from other languages picked up in the Jewish diaspora mark “Jewish” minority languages. The history of exile is etched into Jewish languages.

Here are six Jewish languages, spoken amongst Jews as a way of preserving their communities through the years.

Yiddish

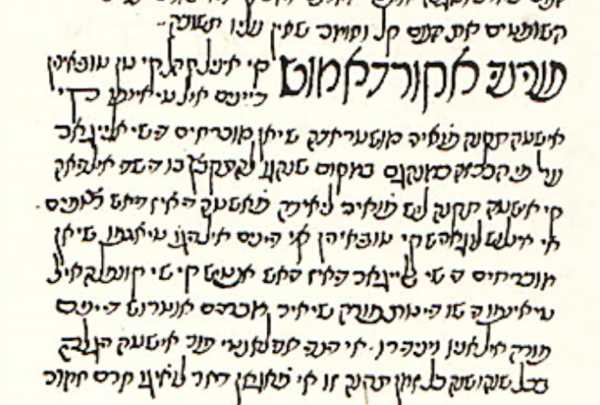

Yiddish evolved among Jewish communities in Slavic and Germanic-speaking lands in the Middle Ages. Incorporating German, Hebrew, Aramaic, Slavic and other language elements, Yiddish is written using Hebrew letters. It was widely spoken in central and eastern European communities from the early Middle Ages until the decimation of Jewish communities in the Holocaust, and continues to be spoken in some Jewish communities in Europe, Israel, and in North and South America today.

In time, a number of different Yiddish dialects arose in Jewish communities throughout eastern Europe. “In each new setting elements from local vernaculars have been absorbed, modified to suit the Yiddish idiom,” noted historians Mark Zborowski and Elizabeth Herzog. “Whoever knows Yiddish can understand the Yiddish of anyone else, even though some of the words may be incomprehensible. Yet each region has its own accent and idioms, which can be recognized and identified.” (Quoted in Life is With People: The Culture of the Shtetl by Mark borowsky and Elizabeth Herzog, Schocken Press: 1952.)

Ladino

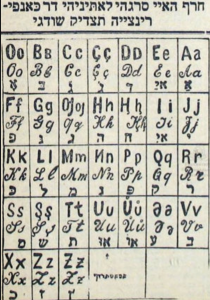

Ladino – sometimes variously called Judeo-Spanish, Judezmo, Judio, Jidio, or Spanyolit – is a language written with Hebrew characters that has been spoken by Sephardi Jews around the world for generations. It has its origins in Medieval Spain where the country’s large, vibrant Jewish community developed a unique way of speaking, blending Hebrew and even some Arabic words with Medieval Spanish.

Facing persecution from Islamic rulers in Spain, some Spanish Jews moved to North Africa in the 1300s and 1400s, bringing Ladino with them, establishing Ladino-speaking communities in Morocco.

When Spain was unified under Catholic rule in 1492, the monarchs King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella marked the milestone by forbidding any Jews to live in the country on pain of death. 200,000 Jews fled the country, bringing Ladino with them.

Ladino-speaking Jewish communities existed for hundreds of years in North Africa, Yugoslavia, Romania, Greece, Bulgaria, Turkey, Egypt, and the Land of Israel. Through the years, local variants incorporated new linguistic elements from Turkish, French, Arabic and Italian. Today, Ladino is still spoken by thousands of Jews, many of them elderly.

Listen to this beautiful Ladino wedding song, Bayla, Bayla (Dance, Dance):

Yevanic

Jews living in the northern regions of Greece developed their own language called Yevanic, also known as Judeo-Greek. The area was home to Romaniote Jews. Prof. Mary Connerty explains “they weren’t Sephardi nor Ashkenazi,” but a separate group of Jews who traced their origin to Jews from the ancient Byzantine empire.

Romaniote Jews developed their own dialect of the local Greek language; Prof. Connerty believes that became more distinct and changed into Yevanic during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. “Beginning with the Ottoman invasion (the Ottoman empire captured Athens in 1458), the language started changing,” Prof. Connerty explains. The local Jewish dialect evolved into something that was unintelligible to non-Jewish Greek speakers. The name Yevanic derives from the Hebrew word for Greece: Yavan.

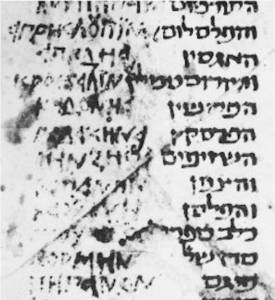

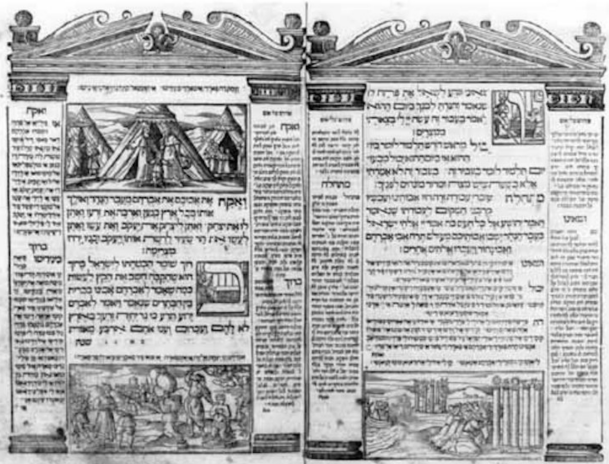

Yevanic contained many Greek words and also incorporated Hebrew, Arabic and Italian. It was traditionally written using Hebrew letters, though some Jews began to switch to writing the language using Greek letters in the 1800s. Romaniote Jews prayed from Jewish prayer books written in Yevanic. There were also some small communities of Yevanic speakers in Turkey. The Constantinople Pentateuch (Jewish Bible) is one of the oldest surviving books written in Yevanic, dating from 1547.

Yevanic contained many Greek words and also incorporated Hebrew, Arabic and Italian. It was traditionally written using Hebrew letters, though some Jews began to switch to writing the language using Greek letters in the 1800s. Romaniote Jews prayed from Jewish prayer books written in Yevanic. There were also some small communities of Yevanic speakers in Turkey. The Constantinople Pentateuch (Jewish Bible) is one of the oldest surviving books written in Yevanic, dating from 1547.

“There is still a tiny population of Yevanic speakers in Turkey,” Prof. Connerty explains, “and a few still in Iran.” She estimates that only a few hundred people speak Yevanic today. In northern Greece, there were about 10,000 Yevanic speakers on the eve of World War II. After the Holocaust, just 149 Yevanic speakers had survived. Today, the language is kept alive by a few families in Jerusalem and New York – and by scholars who continue to research Yevanic and other small Jewish languages.

Bukharian

For generations, Bukharian Jews live in scattered communities across Central Asia, primarily in present day Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. They trace their history back to Biblical times, when King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylonia conquered ancient Israel, destroying the first Jewish Temple in Jerusalem in 587 BCE, and exiled many Jews north into Babylonia. Although many Jews soon returned to Jerusalem and other Jewish lands, some Jews remained in exile, migrating even further north into Central Asia.

These Jews were sometimes known as Bukharian Jews because many lived under the reign of the Emir of Bukhara. Jews often called themselves Isro-il (Israelites) or Yahudi (Jews). They developed a distinct dialect of the local Tajik language which incorporated many Hebrew words, as well as language elements from elsewhere in Central Asia, and became known as Judeo-Tajik. It is also known as Bukhori or Bukharian. Bukharian became the first language for many Jewish communities in the area. Even when they were living in areas where their non-Jewish neighbors spoke Uzbek, not Tajik (which was much more similar to Bukharian), Bukharian Jews would communicate among themselves using Judeo-Tajik, or Bukharian.

In the late 1800s, many Bukharian Jews began immigrating to Israel. The Bukharian Quarter in Jerusalem became a thriving center of Bukharian culture. Rabbi Shimon Hakham, a Central Asian-born Bukharian Jew living in Jerusalem, translated many works into Bukharian and sent them back to his co-religionists in Asia. The Bukharian language, which had been primarily oral for centuries, began to develop a literary character in the Jewish state.

Between 1910 and 1916, a Bukharian-language newspaper called Rahamim was published, first in the town of Skobelev and then in Kokand, both in Uzbekistan. Another Bukharian language newspaper called Roshani (“Light”) ran from 1920 to 1930; in 1930 it changed its name to Bajroqi Minat (“Life of the Workers”) and continued running until 1938. During this period, Jewish schools in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan taught students in Bukharian, using Bukharian-language schoolbooks. This period also saw a transition from using Hebrew letters to write Bukharian texts to using Latin or Cyrillic letters instead.

Today, there are over 200,000 Bukharian Jews: many live in Israel and the United States. While Bukharian is no longer widely spoken, many older Bukharian Jews continue to remember and speak this distinctive Jewish language.

Watch an interview about Bukharian conducted in the language:

Judeo-Arabic

Distinct forms of Arabic spoken by Jewish communities in the Middle East began to evolve as early as the 8th century, according to New York University Prof. Benjamin Hary. He spoke with Aish.com, describing various versions of Judeo-Arabic as a “language variety” rather than a fully distinct language. “I consider Judeo-Arabic in general a language variety that has its own history and variety all the way from the 8th century until today – and in the past two to three hundred years local varieties have developed in Yemen, the Maghreb, Iraq, and Egypt that are unique to this local variety.”

One of the most distinctive aspects of all these diverse Judeo-Arabic dialects is the use of Hebrew letters – rather than Arabic – to write many Judeo-Arabic texts. Another difference from non-Jewish forms of Arabic is pronunciation. Prof. Hary gives the example of Egyptian Judeo-Arabic: Jewish speakers use a long “oo” vowel sound whereas standard Egyptian pronunciation would say “i”. In Yemen, Judeo-Arabic dialects sounded even more distinct from the language spoken by non-Jews. at times employing radically different pronunciation from that of local non-Jewish Arabic speakers. Judeo-Arabic dialects also incorporate Hebrew and Aramaic words, as well sometimes as older Arabic words that have fallen out of use in the wider non-Jewish population.

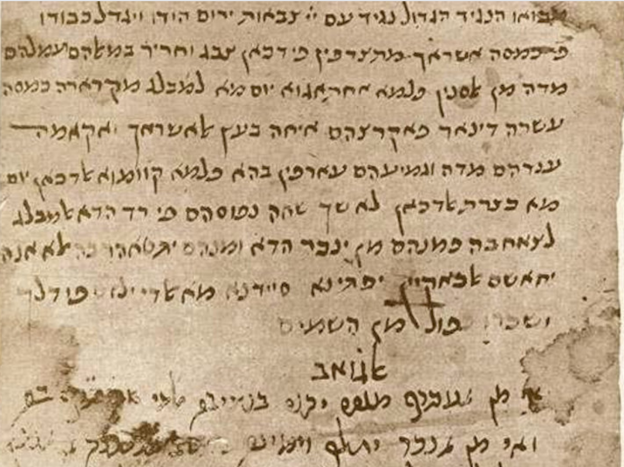

Prof. Hary notes that some of the most notable works of Jewish literature were written in Judeo-Arabic. Judah Halevi (1075-1141), for instance “composed his 12th-century classic work, The Kuzari (Kitab al-Xazari), in a part of the Iberian Peninsula that had recently been re-conquered by Christians, but he nonetheless wrote it in Judeo-Arabic, the language of the educated Jewish classes.” Maimonides’ wrote his classic Jewish work Guide for the Perplexed in Judeo-Arabic while he was living in in the late 1100s, Prof. Hary notes; the name in Judeo-Arabic was Dalalat al-Ha’irin.

Judeo-Italian

n the Middle Ages, Italian Jews developed a unique mode of speaking known today by scholars as Judeo-Italian. Written in Hebrew letters, Judeo-Italian flourished after Jews were confined to small ghettos: all-Jewish neighborhoods in Italian towns where Jews were forced to live. Prof. Sandra Debenedetti Stow, who retired after a career teaching at Israel’s Bar Ilan University, recently shared her research into this distinctive language with Aish.com.

Since Italian Jews were so confined in the Middle Ages, the language traditions they developed were intensely local. “What the Jews spoke and wrote was mainly the dialect spoken in their places of residence, so we speak of Judeo-Roman, Judeo-Piedmontese, Judeo-Venetian and so forth,” Prof. Stow explains. Italian Jews incorporated “Italian archaic terms and… the presence of Italianized Hebrew terms.”

Judeo-Italian used “verbs like ‘achlare’ (to eat), from the Hebrew leechol and the verbal ending -are, ‘lechtire’ (to go) from the Hebrew lalechet, and the ending ire, ‘dabberare’ (to speak), from the Hebrew ledaber, adjectives like ‘ammazzallato’ (lucky) from the Hebrew mazal,” Prof. Stow explains. Some Hebrew terms became adapted to Italian linguistic components too. Prof. Stow notes that talledde was a Judeo-Italian form of the Hebrew word tallit (prayer shawl).

Some Judeo-Italian words were interesting syntheses of Italian and Hebrew terms. Sone meant anti-Semite in Judeo Italian: it came from the Hebrew word sone (hater). Marorre meant an ugly thing in Judeo Italian; it was derived from the Hebrew word for bitter, maror.

Beginning in the Renaissance, Judaic languages in Italian became more Italianized; soon they were simply dialects of local forms of Italian. “Today there are no genuine speakers of Judeo-Italian dialects left inside of Italy,” Prof. Stow notes, “and to the best of my knowledge there aren’t any speakers outside of Italy.” However, in Rome today there is movement among some younger Jews to revive Judeo-Italian and its traditions.

Today, most of these Jewish languages – and other even smaller and lesser known Jewish languages – are considered endangered, their native speakers aging and dwindling. In part, this abandonment of traditional Jewish languages reflects the robust state of Israel as the homeland of the world’s Jewish communities. As Jews have moved to Israel from across the globe, their children grow up conversing in Hebrew. In some cases, Jews have abandoned their traditional languages as anti-Semitism decreased and Jews were allowed to socialize and educate their children in their countries’ dominant languages.

These Jewish languages reflect the history of our ancestors around the world. The poetry, songs, sayings and writings in Jewish languages are a crucial record of how our ancestors lived; they are a tribute to the rich Jewish lives that our forbearers led.

credit to aish.com