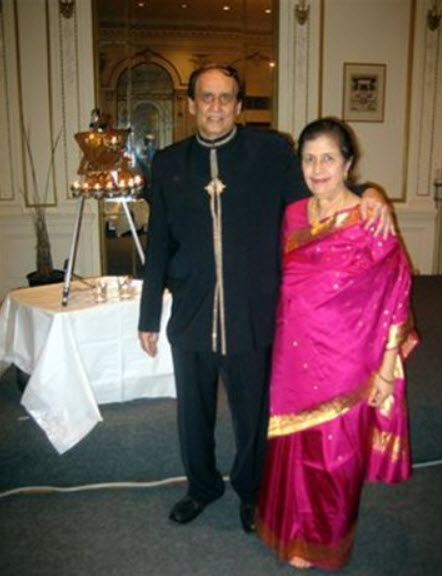

Romiel Daniel was used to leading prayers long before he became a rabbi.

Growing up in the small, tight-knit Jewish community of Mumbai, Daniel was taught Hebrew and the tenants of the faith. While he was not officially ordained, he regularly lead prayers and assisted at his local synagogue, where several members of his family acted as community leaders, he recalled.

That knowledge came in handy in 1994, when Daniel and his wife Noreen moved to New York after living in the island nation of Mauritius for several years. The family soon joined the Rego Park Jewish Center in the borough of Queens and noticed the style of worship was quite different from the traditions they grew up with.

As members of India’s Bene Israel community — one of India’s oldest Jewish communities — the Daniels were accustomed to conducting their prayers in a way that has been passed down for hundreds of years.

“When I came here, that was an Ashkenazi synagogue,” Daniel said. “The melodies are sung in a very different way. But the Torah is the same, that hasn’t changed at all.”

Daniel, who has two degrees in chemistry, decided to attend Yeshiva University in 1999 to become a cantor. He completed his studies in 2003.

“I became an Ashkenazi cantor,” Daniel said, laughing.

He became the rabbi at his synagogue in 2007 and has incorporated some Bene Israel traditions into his services for his congregation, who are largely of European descent. While Daniel said the Indian Jewish population in the United States number just a few hundred, he regularly conducts services for the about 100 members of the community who live in New York and New Jersey.

“We follow the same practices that we had in India. They are identical to the way we did back home in Bombay,” he explained, referring to the city now known as Mumbai. “If we did a change, they’d probably kill me.”

Those traditions can be seen in the way the Indian Jewish community is planning to celebrate Hanukkah.

Instead of lighting a candle to mark the first night of the festival of lights, Daniel plans to light a small cup of oil inside a menorah that he and his wife brought from India. This year, the community will be commemorating the last night of the holiday at the Indian consulate in New York.

In addition to serving sweets like halva (a dessert made from semolina flour and coconut milk) there are “dishes that were made exactly like we do in India.” One of those is the wine traditionally served during holidays.

“There was prohibition in India for so many years, that in India we wouldn’t have wine,” Daniel said. “We would take dried raisins boiled in hot water and squeeze them and we’d make grape juice. And that’s the wine. And that’s a practice that we still do here.”

CREATING A BLENDED IDENTITY

For many members of the Indian Jewish community, moving to the United States has also meant creating a place in two spaces — the South Asian diaspora and the Jewish community — that may not be familiar with Judaism’s long history in India.

“People would say things like, ‘A Jew from India? How is that possible?” artist Siona Benjamin recalled of the conversations she would have after moving to New York for graduate school in the 1980s. “But Judaism, Christianity, and Islam started in our part of the world. I would constantly remind people that.”

Despite those reminders, Benjamin has had to field the questions many immigrants often face about their traditions and cuisine. “They would ask, ‘did you grow up with matzoh ball soup?’ No, I didn’t. We had rice and halva and things like that,” she said.

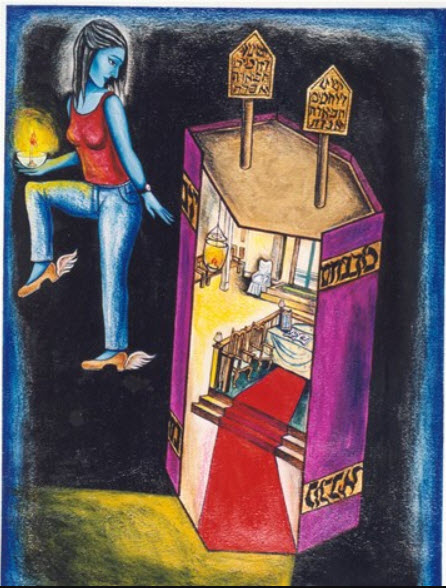

A visual artist, Benjamin said her work changed dramatically after she realized her faith was central to her identity.

Benjamin’s grandmother lived across the street from the Magen Hassidim Synagogue in Mumbai and the artist recalled frequently going to the temple for festivals and holidays. When she received the first of two Fulbright scholarships, she decided to begin documenting the lives of Jews in India.

Through her project “Faces: Weaving Indian Jewish Narratives,” Benjamin set out to tell the story of the Bene Israel. “I photographed them and how they preserved the history of the community,” she said. “They were portrait photographs and then I made 3-D prints out of them.”

The completed project was exhibited in Mumbai’s Prince of Wales Museum in 2013. “All the community came back just to see what I had done,” Benjamin said.

After receiving a second Fulbright, Benjamin traveled to Israel earlier this year to document the stories of the Indian community there. “I photographed the diaspora and how they preserve the history of the community,” she explained. “A lot of my family, they immigrated to Israel.”

After receiving a second Fulbright, Benjamin traveled to Israel earlier this year to document the stories of the Indian community there. “I photographed the diaspora and how they preserve the history of the community,” she explained. “A lot of my family, they immigrated to Israel.”

Like many immigrants with roots around the world, Benjamin and other members of the community sometimes struggle to define where they are from. For Benjamin, the question reflects the history of her community.

“I do feel a deep connection to Israel. I do feel the same way of ‘where do I belong?” Benjamin said. “Am I Indian? Is America my home? Is Israel? Home is everywhere and nowhere.”

credit to nbcnews.com