When the pandemic hit, Edward Ilyasov was in a bit of a pickle.

The 29-year-old resident of Queens, N.Y., had submitted his letter of resignation with plans to travel the world, starting with Israel. His last days at his well-paying job in finance were supposed to be during the latter part of March 2020, and he planned to paint a person a day as he gallivanted. Yet with restrictions on travel due to COVID-19, he realized that he’d have to scrap his artistic dream. His employer allowed him to return, and he began working remotely.

Despite the fact that he was succeeding in New York—his Bukharian family came from the former Soviet Union in 1991—the sales trader for interest-rate derivatives said other young Bukharians were getting boxed into the same job fields.

“I noticed a lot of Bukharian people went for the same careers over and over again, and it bothered me,” he explained. “If they didn’t go to school, they were barbers or jewelers. If they went to school, they did dentistry, pharmacy or nursing—always the same story. Since I chose a career in finance, I thought it would be important for young Bukharians to have a taste of different careers available to them.”

He hosted events with Bukharians who were involved in atypical careers, including a magician, a female dermatologist and an architect, he said.

One speaker offered him a piece of advice: “If you have an opportunity to do the opposite of what you normally do, do it,” he recalled the person as saying.

He soon got an adjunct professor position at Queens College, based on his master’s degree from Columbia University in financial engineering.

“I realized in one math class that I taught, I felt more fulfilled than working on Wall Street for four years prior,” he said.

Of course, adjunct professors make scant money. Still, he said there was something missing from his finance job, despite making “well over six figures.”

The turning point was a meal that harkened back to his Bukharian roots.

“My aunt cooks well and served me Plov [a Bukharian dish of rice with meat, carrots and oil] with a pickle that was especially delicious,” he said. “I tried it and was blown away. I asked where she bought it, and she said she made it. She gave me a vague recipe.”

‘Follow your passion’

And so, he started making his own kosher pickles, and at first, they were not impressive. Through trial and error, they became better and better—so much so that he made an Instagram video where he bit into a pickle, and people thought the audio of the crunch from the bite was fake. Neighbors tried them and fell in love with them, and told him to sell them.

“I developed a waiting list, and I couldn’t keep up,” he said, adding that at one point 600 people waiting for his vinegary fare.

He hired a few people and moved from the kitchen to the basement. As a self-described foodie, he said he used to always watch the “Food Network.” He has also been to 21 countries.

“At one point, my boss said, ‘We’ll be coming back to the office, Eddie. You’ll have to choose between the pickles or coming back,’ ” he recalled.

Since he believes he’s caught lightning in a bottle—simply from posting people eating pickles on Instagram—he chose to see if he could make a go of the pickle company. He sells a jar of 4.5 pickles for $8 and a jar of habanero pickles for $10. He uses a mashgiach (“supervisor”) to make sure the pickles are kosher, especially the dill, under OK supervision, he said. He no longer teaches any math classes.

He said as an Ivy League graduate who used to make a great salary, it wasn’t an easy sell to tell his father he’d be selling pickles.

“My mom said, ‘follow your passion,’ ” he said. “My dad said, ‘Are you crazy?’ There were a lot of arguments and tense moments.”

‘I wanted to have more meaning’

He admitted that it took a year to perfect the recipe.

“Life is funny,” he said. “When I was broke, all I wanted was money. Now that I have money, I wanted to have more meaning. I wanted to do something I loved. When you give someone the best pickle they ever had in their life, it’s priceless. When they pick up a jar and smile that they will have it on their Shabbat table, it’s a golden feeling.”

The name of the company? Uncle Edik’s Pickles.

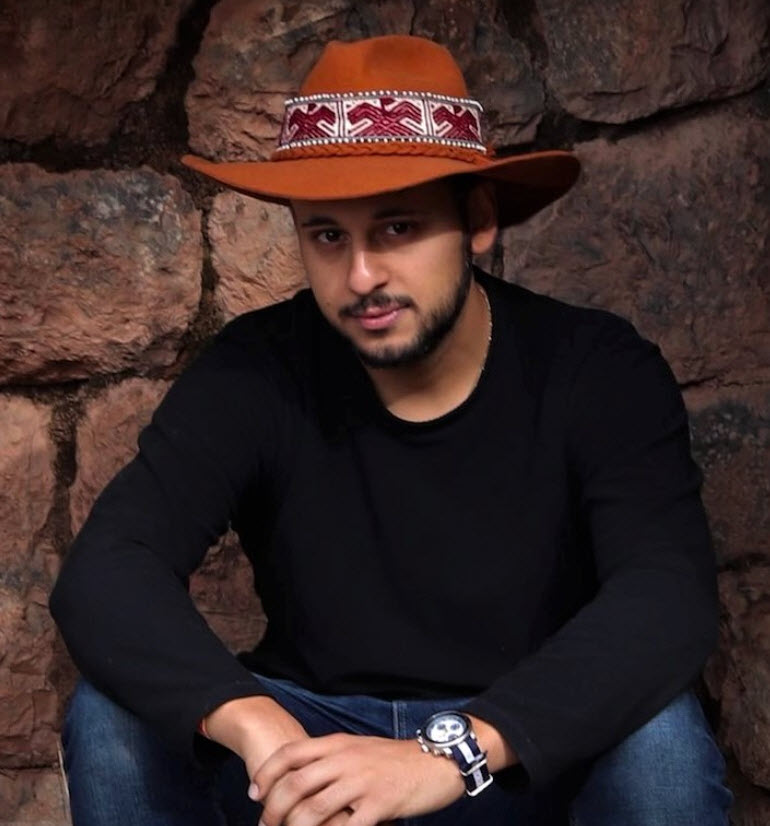

The logo shows a person with a hat with a mustache underneath. He said some have incorrectly thought the logo is Mexican. He explained that he wore a hat when traveling in a sunny climate, where he met someone that was on vacation for a month who had three ice-cream stores. The person seemed happy, and it made him think his pickle idea had a shot.

While it might seem as if people wouldn’t have money to afford expensive pickles, he said in his community, people have disposable income and want to spend it on something different.

He noted that one problem he’s encountered is inflation and the rising cost of glass jars for the pickles.

“When I started making a lot of them, I was spending a dollar per jar,” he said. “Now there’s a shortage, and it’s hard to get jars. There are fewer workers, and the demand is crazy. I just had to buy 10,000 jars at $1.50 each. It’s unheard of. A year ago, they were 80 cents each. I’m taking the hit, but I’m not raising my prices because I’m just starting out in the business, and I don’t want to scare people away—and $8 is already a lot for a jar of pickles.”

He said he’s sold about 10,000 jars of a total of about 45,000 pickles.

He said his philosophy is simple.

“Most people are used to half-sour or sour,” he said. “These are fresh, crunchy and have dill in them.”

Ilyasov also plays guitar, and at Jewish singles events, he said, some women did a double-take when he said he makes pickles, though many thought it was cool. He said about 60,000 Bukharian Jews live in New York City—most of them in Queens—and that a good number of them know him. Many in the community enjoy vodka with pickles, he noted.

His store in Fresh Meadows, where he features some of his own paintings and those of other artists, is self-funded; he said he has turned down investors because he wants to see how the business grows.

“A lot of people told me I’m crazy to give up a Wall Street job for pickles, including my boss, who is a great guy,” he said. “But I’m young, I have a product that people like, and I think I’d be crazy if I didn’t give this a legitimate shot.”

credit to jns.org