Don’t believe Borat about Kazakhstan’s hatred of Jews. The reality is rather different.

Sasha Baron Cohen portrays Borat, a bumbling Kazakh who’s racist, sexist and virulently anti-Semitic. He jokes about Kazakhstan being a nation where Jews are hated. Yet the reality is very different. Long abused by the Soviet Union, Kazakhstan today is a pluralistic country with a small but flourishing Jewish life. Here are six facts about Kazakhstan and Jews.

Early Russian Army Conscripts

Kazakhstan is a massive country in Central Asia. For years, it was sparsely inhabited by nomadic tribes; in fact, the word Kazakh comes from the Turkic word “Kaz,” meaning wander. In ancient times, much of today’s Kazakhstan was ruled by Persia; in the Middle Ages it was governed by Genghis Khan. Jewish merchants settled in the town of Turkestan in this period, and built a synagogue whose remains can still be seen today.

In the 1700s, Russia began advancing into Kazakh territory. The atmosphere in Russia was full of change: Czar Nicolas I fancied himself a reformer and wanted to make sweeping changes to Russia’s large Jewish community. In 1827 he instituted a brutal draft forcing Jewish communities to provide boys for the Russian army. Numbers varied in different communities, but averaged about four boys each year per 1,000 Jews. Service in the Russian army was all-consuming; conscripts had to serve for 25 years. Unlike other soldiers who didn’t have to join the army until age 18, for Jews the draft age was lowered to 12.

Though Jewish conscripts were technically allowed to practice their religion, the reality was very difficult. Taken from home, brought up among anti-Semitic soldiers and denied contact with Jewish communities, most Jewish soldiers in the Czar’s army lost their connection to Jewish life. Even worse, if any soldier married and had children, their offspring became property of the Russian state and were mandated to attend Russian military schools.

Despite these incredible hardships, some Jewish Russian recruits who found themselves stationed in Kazakhstan did form Jewish communities. Clusters of Jews lived in several towns across Kazakhstan, praying in private homes and living low-profile Jewish lives. In Almaty (then known as Verniy), the largest town in Kazakhstan, local Jews opened a synagogue in 1884 – Kazakhstan’s first since the Middle Ages. Located in a small wooden building, it served about a hundred Jews, most soldiers and veterans.

Exiled to Kazakhstan for Practicing Judaism

Under Soviet rule, Kazakhstan was exploited, starved and used as a dumping ground for political prisoners. Kazakhstan is a vast land, encompassing mountainous areas as well as inhospitable deserts and steppes. The harsh terrain of Kazakhstan’s interior was soon dotted with a vast system of gulags, political prisons where millions of dissenters and ethnic minorities were imprisoned, tortured, and often died. One of the gulags, at the Karaganda coal mine in Kazakhstan, was 300,000 square miles – about the size of France – and processed over a million political prisoners. Aleksander Solzhenitsyn, who wrote The Gulag Archipelago, was imprisoned in Kazakhstan.

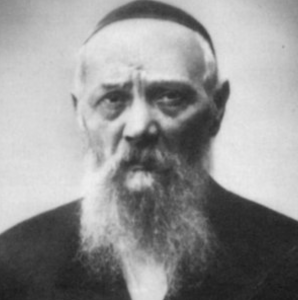

Among the dissenters sent to gulags in Kazakhstan and elsewhere were Jews who insisted on clinging to their religious observance in defiance of Soviet law. One of these Jews was Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson, the father of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson of blessed memory, the late Lubavitcher Rebbe.

Born in 1860, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak was a brilliant scholar; his wife Chana was also a distinguished intellectual and together they helped Jewish life continue in the Soviet Union. The couple became the chief rabbi and rebbetzin of Dnepropetrovsk (then known as Yekatrinoslav) in Ukraine. Religious life was strictly controlled, and Rabbi Levi Yitzchak risked his life to build a secret mikveh (Jewish ritual bath), and to perform secret Jewish weddings. Jews at the time were allowed to bake matzah, but were forbidden from having rabbinic supervision to make sure it was kosher. Rabbi Levi Yitzchak interceded with the authorities to gain permission to ensure that his community’s matzah was kosher for Passover.

The Jewish community in Jaffa, in what today is the State of Israel, invited Rabbi Levi Yitzchak and Chana and their family to move there and lead the community, sending visas for them and the couple’s four sons. But the Schneerson family stayed in the Soviet Union, working to help keep Jewish life going. Just before Passover in 1939, Stalin sent the fearsome secret police to Rabbi Levi Yitzchak’s house. They ransacked his library, then arrested the rabbi for activities supporting Jewish life. He was sent to one of the notorious gulags in Kazakhstan, where he was tortured over a period of nearly a year.

Afterwards, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak was banished to the Kazakh town of Chi’ili. His wife Chana joined him. Eventually, they were allowed to move to Almaty where they led the Jewish community. Rabbi Levi Yitzchak passed away in Almaty in 1944. In August 2020, the Government of Kazakhstan designated Rabbi Levi Yitzchak’s grave a national heritage site.

Bukharian Jews

Not all the Jews of Kazakhstan are Russian. Kazakhstan borders the nations Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to the south; these nations are home to Bukharian Jews, some of whom have made Kazakhstan home.

Bukharian Jews trace their history to 539 BCE, when King Cyrus conquered Persia, ending the Jewish exile there that occurred a generation before when Nebuchadnezer conquered the Land of Israel and destroyed the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem. King Cyrus allowed Jews to return to Israel, where they promptly began work on the Second Temple. Some Jews remained in Persia, however. Over time, groups of Persian Jews moved further north, into the Central Asian areas that today form the Republics of Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and neighboring regions. In time, these “Bukharan” Jews – named after a town called Bukhara in Uzbekistan where a Jewish community settled – became cut off from other Jewish populations. They spoke a language called Bukhari or Judeo-Tajik, which was heavily influenced by Tajik language groups and which also incorporates many Hebrew words,

Facing Muslim anti-Semitism and a forbidding, inhospitable terrain, Bukharan Jews gradually became spiritually and culturally degraded. That changed in 1793, when a Moroccan Jewish leader, Rabbi Joseph Maman al-Maghribi, visited the area and decided to stay to help the Bukharan Jewish community. Rabbi Maman established the Hibbat Zion – “Love of Zion” – movement, which sent thousands of Bukharan children to Jerusalem, first for visits, and then in time to move there permanently. By the time of the Russian Revolution in 1917, there was already an established Bukharan community in Jerusalem. Following the revolution when Central Asian Republics came under Soviet rule, many more Bukharan Jews left to join their brethren in the Land of Israel. Some smaller groups of Bukharan Jews migrated further north, settling in Kazakh towns and villages, as well.

Haven During the Holocaust

In his latest movie, Sasha Baron Cohen has Borat describe the Holocaust as a high point in Kazakhstan’s history. The comedian had a point, but it’s the opposite of his joke: the terrible years of the Holocaust were a high point in Kazakh history, when it welcomed over 8,500 Jews who were fleeing from the Nazis.

These desperate Jews came from across Russia and Russian-held Poland. Kazakhstan was remote and impoverished, but it offered a safe haven far from Nazi aggression. Prof. Anna Shternshis, a Professor of Yiddish Studies and the Director of the Anne Tanenbaum Center for Jewish Studies at the University of Toronto, uncovered a World War II era Yiddish song called Kazakhstan, which describes what Prof. Shternshis has called the “melting pot” of Jewish life in Kazakhstan during the Holocaust. (She included Kazakhstan in a Grammy-winning CD she produced called Yiddish Glory: The Lost Songs of World War II in 2018.) Jews from Poland and the Soviet Union, and also Jewish political prisoners who’d been released by the Soviet authorities from gulags in Kazakhstan all mingled together in Kazakhstan during the war.

“I have suffered from when I was born endlessly,” the song begins, before going on to describe the warm welcome Jews who were fleeing the Holocaust received in Kazakhstan. The song is a testament to the many different ethnic groups who called Kazakhstan home. “A Kazakh, an Ossetian, a Uigher and a Georgian, Ukrainian, Roma, Russian, Kalymyk, Tajik, Belarussian…. Now, our family has another member: You are our brother, (dear) Jew.” Most of the Jews finding refuge in Kazakhstan spent the war in Almaty, Kazakhstan’s largest city.

Hidden Jews

Though the Soviet authorities who ruled Kazakhstan forbade most forms of Jewish religious expression, Jewish life did exist in Kazakhstan, thanks to one incredibly brave Chabad rabbi from Brooklyn, Rabbi Hillel Liberov. In 1944, after Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson died, Rabbi Liberov realized that the Jews of Kazakhstan needed a leader, and he moved to Almaty. From 1944 until his death in 1982, Rabbi Liberov served as the unofficial chief rabbi of Almaty. He led secret Jewish services, and slaughtered animals according to Jewish kosher law so Kazakh Jews could have some kosher meat for Shabbat and holidays. It was incredibly dangerous work: his children back home in Brooklyn didn’t know if they’d ever see him again. He faced arrest at any moment. Yet his heroic efforts kept Jewish life alive in Kazakhstan.

Many Jews were sent to Kazakhstan during the Soviet era to work on mining and nuclear testing projects in the Republic. Though Jewish life was severely repressed, some Jews did manage to live Jewish lives in secret. It’s unknown today how many thousands of Jews risked torture and death to attend secret religious services and celebrate illicit Jewish weddings during this period.

Flourishing Jewish Life Today

Today, a sizable community of up to 20,000 Jews call Kazakhstan home. (Different organizations cite different numbers; some estimate that the Jewish community is as small as 3,500.) The Chief Rabbi, Yeshaya E. Cohen, first moved to the country in 1994. “When I arrived in Almaty, it was an entirely different atmosphere” from the rest of the Soviet Union, he’s recalled, noting the “kind and friendly people” in Kazakhstan.

Almaty has the country’s largest Jewish community, and smaller Jewish populations are found in regions including Astana, Semiplatinsk, Dzhambul, Uralsk, and Karaganda. Over twenty Jewish communal organizations contribute to Kazakh Jewish life, often with help from larger Jewish communities worldwide. In Karaganda, for instance, the thousand-strong Jewish community is aided by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC), which runs a Jewish community center. Local Jews attend cultural events, take Jewish classes, and also volunteer distributing food and supplies to impoverished local Jews.

During Soviet times, Kazakhstan suffered enormously. Many of the Soviet Union’s nuclear tests were completed in Kazakhstan, and much of the country was filled with gulags. Ethnic Kazakhs were treated as second class citizens in their own home, with Russians being favored. Kazakhstan declared independence after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, and since then, it has seen extraordinary change – including the flourishing of Jewish life, which had so long been suppressed by Soviet authorities.

Rabbi Cohen notes that far from being the Jew-hating caricature of Borat, Kazakhs are tolerant to the Jewish minority in their midst. Hanukkah, especially, is a wonderful holiday in the country, and often coincides with Kazakhstan’s Independence Day. “It’s a reason to be twice as happy,” Rabbi Cohen explains, “for we still remember the Soviet times when everybody had to be the same, as people were afraid to express themselves in their clothes, thoughts and beliefs.”

Today, Kazakhstan’s Jews are free to show their Jewishness. A new generation is growing up with synagogues, Jewish schools, and Jewish classes open for the first time in the country in years.

credit to aish.com