My family comes from a state that doesn’t exist anymore. Its official name was the Emirate of Bukhara, and it occupied the land that is now known as Uzbekistan. Beyond that (part of which I had to look up on Wikipedia), I don’t know much. I know that my saba and savta — or my grandparents — can speak Bukharian, the language of Bukhara, as well as Hebrew, Aramaic, Arabic, Ladino and English. And I know that they left me with English, with hard consonants instead of the lilting syllables that I’ve tried (and failed) to imitate since I was a child. I know that my last name is a relic of Rabbi Shimon Hakham, who was the first to translate religious books from Hebrew into Bukharian. He served as an essential gateway to knowledge that was otherwise inaccessible; to honor him, my family changed our last name, twisting it to fit into the unaccommodating mouths of people who feel no obligation towards understanding the name and laugh at the strange word, even in its guttural “ch”-less, Americanized version.

I know that a select few times each year, my savta cooks a Bukharan dish that I don’t know how to spell, but it’s delicious, so the name never really mattered. It’s a dumpling filled with seasoned beef and served in a broth, and it’s the only way that she can get all of our family under one roof. One time, we spent an entire day together as she tried to teach me how to cook it. But it proved too hard for her to explain to an impatient 13-year-old how she intuitively knows how much seasoning is necessary, so we gave up. Every year, she cooks it less and less, but we all pretend that isn’t happening because no one can make it like her. This dish is our only true connection to a home that I didn’t know even existed until a few years ago (when I asked where the dumplings came from).

Currently, there are around 200,000 Bukharan Jews in the entire world. Around 1,500 of those Jews remain in Uzbekistan. The rest, including my family, were driven out by pogroms. The majority (around 100,000), my family included, immigrated to Israel. From there, around 70,000 (my family included), immigrated to the United States. The crazy part: Of those 70,000 Bukharan Jews, 50,000 reside in Queens, New York (which I have never visited). My family, along with no other Bukharan Jews that I am aware of, live in Illinois.

It is in this context that I entered Yale, conscious of an entire aspect of my identity that mainly resides less than 100 miles away from me, an aspect of which I have limited knowledge. And quite honestly, I was not sure whether it was knowledge worth pursuing.

Enter Remapping America, a Windham-Campbell Festival event last Friday featuring Rebecca Solnit: feminist, writer, badass, and apparently a cartographer as well, because she does everything else so she might as well do that, too.

It was a long day, and I’m ashamed to say that, sitting on the couch in that lukewarm room, I felt the allure of sleep more strongly than I would have liked. The words coming out of her mouth were fascinating, and yet, I could not, for the life of me, stay awake. A late night, even if that late night is spent writing a paper, has its consequences. And mine was that I was in the presence of someone for whom I had immeasurable respect and admiration, and my eyes just would not stay open. That is until she mentioned Queens, New York.

I had never met another Bukharan Jew that was not a member of my immediate family and ever since I discovered last year that nearly all of us reside on Long Island, I have had this hope that anyone who mentions the borough will also mention its Bukharan Jew population. It’s slightly irrational — more than slightly, considering that very few people (including myself until relatively recently) know what Bukhara even is. And yet, Rebecca Solnit was describing Queens in relation to the plethora of languages flourishing within its borders. It felt as though maybe, just maybe, I had found a connection. I didn’t feel like sleeping anymore.

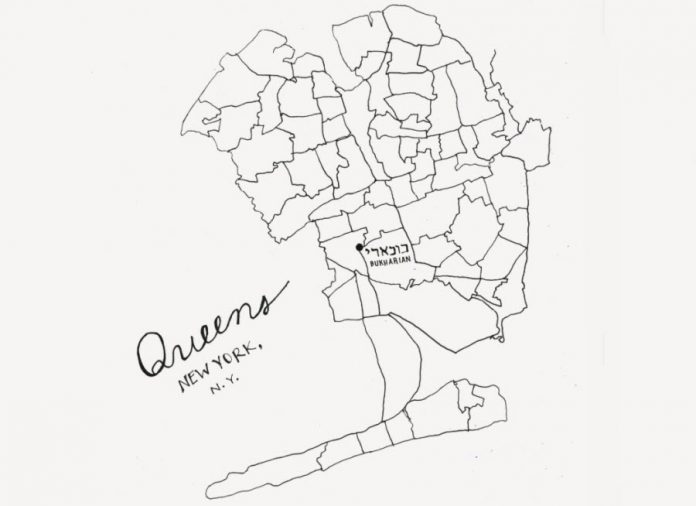

Sure enough, she passed a map of languages spoken within Queens around the room, and there, right smack in the center, was “Bukharian.” It was a weird feeling to see it in writing, and I realized that I had never encountered the word before in a search that wasn’t initiated by myself. It made it real, like this whole culture was something that I had made up in my head until I saw it, in writing and in person. We exist. I didn’t know how much I thought that we didn’t until I showed it to my friend and she confirmed that Bukharian was, in fact, on the map, right smack in the center. I wanted to cry: from happiness or sadness, I’m not really sure.

Solnit’s talk was absolutely incredible, but what I really remember, more than the words she spoke, was that map, and the feeling I had when I saw myself reflected in it.

Sometime in the next few weeks, I’m going to visit Queens. I’m going to find the Bukharan Jewish museum that apparently exists, the room dedicated to Rabbi Hakham and the extended family who doesn’t know that they have American relatives outside of New York. And maybe, a few days after I get back and someone asks for my last name, I’ll pronounce it correctly— guttural “ch” and all.

Madison Hahamy | madison.hahamy@yale.edu .