(Judeo-Tadjik, Judaeo-Tadjik, Bukhori, Bukharian)

Description by Chana Tolmas

Judeo-Tajik is a Persian language spoken and written by Bukharan Jews in the 18th to 20th centuries. Bukharan Jews have lived in Central Asia, in areas currently in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, since antiquity, most recently in cities such as Bukhara, Samarkand, Tashkent, and Dushanbe. Due to immigration and language shift, Judeo-Tajik is currently endangered, spoken by small communities in Central Asia, Israel, and the United States.

History

During the second half of the eighteenth century and the early nineteenth century, political and territorial changes in Central Asia led to the gradual transformation of Judeo-Persian into Judeo-Tajik. Initially, this language was used by Bukharan Jews for communication within the family and community. In the late nineteenth century, however, Judeo-Tajik developed into a literary language thanks to the enterprise undertaken by Rabbi Shimon Hakham (1843–1910), the founder of a literary school in Jerusalem. The active members of this school published the first translation of the Bible into Judeo-Tajik. They also translated numerous other religious and secular works from Hebrew into Judeo-Tajik.

In the early twentieth century, this Jerusalem-based enterprise published important literary works written in Judeo-Tajik, dictionaries in various languages, and more. Most of these books were sent to Central Asia, where many Bukharan Jews still lived at the time. During this period, no books in Judeo-Tajik were published in Russia. A single newspaper, רחמים (Rahamim) (1910–1916) was published in the city of Skobelev in the district of Fergana and later in Kokand.

Following the rise of the Soviet regime, hundreds of schoolbooks were printed in Central Asia for a network of Jewish schools where classes were taught in Judeo-Tajik. Between 1920 and 1930, this language gave rise to works of poetry and prose, plays, the newspaper “Roshnaji” (Light) (1925-1930), whose name was later changed to “Bajroqi Mihnat” (1930-1938) (Workers’ Flag), and socio-political reviews including “Hajoti Mihnat” (Life of the Workers), named later “Adabijoti Soveti” (Soviet Literature) (1930-1938). This was the golden age of Judeo-Tajik literature.

Up until 1928, these publications made use of the Hebrew alphabet (Rashi letters were used in writing, while square letters were used in print) and some Jews used the Arabic alphabet, which was used by local non-Jews at that time. These alphabets were briefly replaced by the Latin one, and, in 1938, the republics of Central Asia began transitioning to the Cyrillic alphabet. This change was not imposed on Judeo-Tajik, since the demise of Jewish culture (theaters, newspapers, literary reviews, museums, and so forth) during this period amounted to a death sentence to the literary use of Judeo-Tajik. In 1940, it became forbidden to publish in this language, and Jewish schools switched to teaching in Tajik, Uzbek, and Russian. For the following fifty years, Judeo-Tajik served solely for communication within the family and community. Only a small number of Judeo-Tajik publications appeared in Israel between 1950 and 1980.

With the immigration of Jews from the former USSR to Israel in the 1970s, and even more so in the 1990s, the use of Judeo-Tajik resurfaced in various contexts. This period saw the publication of new Judeo-Tajik dictionaries and anthologies of poetry and prose, the broadcasting of radio programs, and the performance of plays. Judeo-Tajik newspapers printed in Cyrillic letters also appeared.

Some Characteristics of Judeo-Tajik

Judeo-Tajik has a number of unique traits that are not shared by the Tajik language. From a phonological and prosodic perspective, Judeo-Tajik is distinguished by a number of different question and exclamation intonations, as well as by the existence of unique phonemes (the guttural Hebrew letters het and ayin). From a morphological perspective, there are also differences in the conjugation of verbs, such as merum (I will go), which is pronounced meravam in Tajik, or rafsode (he is going) – rafta istodaast in Tajik.

Judeo-Tajik also borrows words from Hebrew and Aramaic that are related to religious ritual, as well as words from the sphere of everyday life. Semantically, most lexemes of Hebrew-Aramaic origin may be classified according to the following categories:

1) Religious terminology:

a) life cycle:

– birth: benzokhor son < בן זכרson + male, masculine; milo < מילה circumcision, sometimes the word misvo < מצווה ‘ religious duty ,good deal’ is used in the meaning of ‘circumcision ; mü(h)el < מוהלcircumciser ; sandoq < סנדק ‘godfather’

– marriage: qudush ‘marriage due to Jewish tradition’ < קידושין (in is omitted) katüvo ‘marriage contract’ < ,כתובה get ‘divorce’ < ,גט haton ‘bridegroom’ חתן ->, kalo ‘bride’ < כלה , shidukhin < שידוכים (Niyazov 1979:94) ‘match-making’ ;

– death: gan’eden ‘Paradise’ < גן עדן, gey(h)inüm ‘hell < גהנום , hashkovo prayer for the deceased among Sephardim < השכבה , lavoyo < לוויה ‘funeral’

b) Jewish holidays:

hanükko‘Hanukkah(feast)’ < חנוכה ; mü’ed ‘Jewish holiday < מועד ‘appointed time, festival(holiday)’ , pisho ‘Passover’ < פסחא , puryo < פורים Purim , sukko ‘Feast of Tabernacles’ < סוכות rüshoshono New Year according to the Jewish calendar < ראש השנה

c) Food:

bosor ‘kosher meat’ < בשר meat’ ; homes ‘leavened <’ ,חמץ lehem ‘bread , לחם > maso < מצה matsa

d) Prayers:

barokho ‘blessing’, ‘grace’ < ברכה , qidusho < qidush + Tajik ending of noun plural form sanctification over wine’ , קידוש > ‘aravit ‘evening prayer < ערבית

e) Community members, fulfilling specific functions:

melamed ‘teacher of a religious school’ < מלמד , hokhom ‘rabbi’, ‘scholar’ חכם >wise man’ ; gabboy ‘Gabbai, president or treasurer of a synagogue’ ; גבאי > hazon cantor <’ ,חזן qasov ‘butcher <’ , קצב shamosh ‘caretaker (in synagogue) , שמש > shühet ‘Jewish slaughterer’ < שוחט

f) Words with abstract meanings:

zekhut ‘right’, ‘merit’ < זכות , gürol fate ’ , גורל emet ‘truthאמת > .

g) Other religious terminology:

qodüsh holy, saint < קדוש , kaneso synagogue Aramaic <, בית כנסת muzo|| mazüzo mezuzah, parchment scroll fixed to the doorpost <, מזוזה sadoqo charity < ,צדקה sefartüro Torah scrolls < ספר תורה status constructus ; te(h)ilim Book of Psalms , תהילים > hevro the name of any organization that helps poor people < חברה company ; hevro-qadisho burial services חברה קדישא ; tifilin phylacteries < תפילין, sisit tassel, ציצית >

There are other groups of Hebrew and Aramaic words in Judeo-Tajik hardly dealing with religion, for example,

2) Family life:

milhomo ‘discord between a wife and a husband’ < מלחמה war ;

mishpoho משפחה > ‘family,’ parnoso ‘family income <’ פרנסה ‘livelihood’, ‘means of support’; sakin ‘knife’ < סכין , shulhon small table < שולחן ‘table’ , zahow ‘gold ,זהב >

3) Description:

akhzor ‘cruel’ <אכזר‘, oni ‘pauper’ < ,עני qamson greed ,קמצן > rosho’‘villain , רשע > sodiq righteous man , צדיק > shüte fool, mad < שוטה mamzer ‘illegitimate child’, ‘cunning man’(7) ,ממזר > züno ‘prostitute < – זונה , batülo ‘virgin , בתולה > ganov ()‘thief < . גנב

4) Set expressions:

a) greetings:

sholüm alekhem ‘peace to you’ < שלום אליכם

shabot sholüm Good Shabbat < שבת שלום

shovu’a tüv ‘good week’ < שבוע טוב

safro tovo ‘good morning’ (See: Babaev, 1991:88);

ramsho tovo ‘good evening’ < (Aramaicרמשא טבא ( (See: Aminüf, 1931:12) ;

b) specific occasions:

– congratulations:

simon tüv ‘congratulations (generally) for the birth of son‘ <סימן טוב good sign

mazol tüv ‘congratulations for the birth of daughter’ < מזל טוב

– wishes:

refuo shalemo ‘complete recovery’ < רפואה שלמה

hayim r’efuo (9) ‘good health’ חיים רפואה > ‘life + recovery

shonim rabüt ‘long life שנים רבות > ‘many years

Hebrew-Aramaic lexemes also occur in:

a) blessings:

‘aynoro’dur boshi ‘be far from evil eye’, ba barokho boshi ‘God bless you’, ba asloho boshi ‘be successful’, sermazol shavan(d) ‘let them be happy’.

b) curses:

elef elef raveton ‘will go (die) thousand and thousand of you’, makhshemo shavi ‘go away forever’, ‘ayn+ayat ever shavi ‘be blind’, khovi meto ravi ‘be dead’.

Euphemisms are expressed by Hebrew-Aramaic elements and word combinations, such as:

bedakse ‘WC’ < בית הכיסא house of the chair

beit-hayim cemetery < בית חייםhouse of living

manüho yoftan ‘die’ < מנוחה rest + Tajik yoftan ‘ find’

nashomo dodan ‘die’ < נשמה spirit’ + Tajik dodan ‘give’.

Sometimes Bukharan Jews used Hebrew-Aramaic elements in their ‘secret’ language when they wanted to cover up something from the host population. There are some groups of words used by Jews in the presence of Muslim speakers of Tajik:

a) numerals of Hebrew-Aramaic origin were most popular:

ehot < אחד one , shinem שניים > two , shalüsho < שלושה three ,

arbo’o < ארבעה four , hamisho חמישה > five , shisho שישה > six

b) word combinations were used:

umüt ho’ülom ‘nation(s) of the world’ < אומות-העולם ,

diburlü ‘say nothing’ < דיבור ‘talk’ + lü < לא‘ not,

nishev shudan < נשב ‘we will sit’ in combination with the Tajik verb shudan ‘ become’ is used in the meaning of ‘disappear’

The Hebrew-Aramaic elements in Judeo-Tajik retained their original meanings in most cases. However, semantic shifts occurred in some Hebrew-Aramaic words. For example:

- barokho < ברנה ‘blessing’ sometimes is used in the meaning of ‘profit’, ‘benefit;

- benodom derives from Hebrew בן אדם ‘‘human being’. Like in Judeo-Spanish (See: Schwarzwald, 1985: 141) the word narrowed its meaning from any person to ‘a well-behaved, considerate person’;

- gaovo ‘vain’, ‘arrogant’ < גאווה pride’;

- osur ‘I swear’ is derived from אסור ‘prohibited;

- shomayim שמיים > ‘heaven’, ‘sky’ changed its meaning to ‘an intoxicated man’;

- malokho – מלאכה is used in the meaning of ‘profit’, ‘yield’;

- yüshvo ‘funeral repast’ < ישיבה ‘sitting’ ;

- ‘asoro עשרה > ‘ten’, the word narrowed its meaning to a ‘quorum for prayer’.

An insult is sometimes expressed by referring to people with Hebrew-Aramaic animal names:

- kalov < כלב dog (in the meaning of ‘ungrateful’) ;

- hamür < חמור donkey (an insult name of host population.)

These words are generally not felt by Bukharan Jews to be foreign elements.

There are some Hebrew stems with morphemes of Tajik origin:

1) hypocoristic forms such as: shedim+cha ‘little devil’, te(h)ilim+cha ‘small Book of Psalms’, Hano+cha ‘little Hana’,

2) plural forms with the help of the suffix -ho:

kühen+(h)o ‘the Cohens’, ovel+(h)o ‘mourners’, hover+(h)o ‘friends’, dor+(h)o ‘generations’;

3) possessive forms :

a) with the help of Persian izafet -i:

– status constructus, where the first member is Hebrew: horow+i Samarqand ‘the rabbi of Samarkand’, hupo+i bachetona (binet) ‘(see) the wedding of your child’; (ba)simho+i shumo ‘(for) your health (joy)’;

– status constructus, where the second member is Hebrew: büy+i rih ‘bad smell’; nü(h)+i ov ‘ninth of Ab’, ‘a fast day’;

rüz+i kipur ‘Day of Atonement’; güsht+i shabot ‘meat for Shabath’

– status constructus, where both members are Hebrew: shabbot+i qüdem (< qodem) ‘first Friday eve after somebody’s

death’,

– status constructus, where first member Aramaic, second – Hebrew: sandoq+i rishon ‘the first godfather’;

b) with the help of Tajik pronominal enclitics: mazol+am ‘my luck’, mazol+at ‘your luck’, mazol+ash ‘his(her) luck’, nishomo+ash ‘its spirit’ and so on;

There are some Judeo-Tajik words produced from Hebrew-Aramaic stems + Judeo-Tajik affixation:

– adjective suffixes: -i , -nok:

ovel+i ‘mournful’, kosher+i ‘kosher food’, derekh-eres+nok ‘respectful’, ovel+nok ‘mourning’

– adjective prefix be- (with the meaning of lack of something):

be+mazol ‘unlucky’, be+gaavo ‘not vain, ‘not arrogant’.

– suffix -gi, forming abstract nouns: ‘oni+gi ‘poorness’

There are some compound nouns in Judeo-Tajik, where one of the stems is of Hebrew-Aramaic origin, and another is of Tajik origin:

kosher+khür (khür – the present stem of the verb khürdan ‘eat’) ‘eater kosher food’, ‘person, who consumes only kosher food’; mahelo+tavli ( tavl < talabidan [J.-T.verb built of Arabic ‘talab’ + J.-T. affixation -i-dan] the present stem of the verb talabidan ‘ask’,’demand’ + suffix – i that forms abstract nouns) ‘asking for forgiveness’.

Some of the verbs in Judeo-Tajik occur with Hebrew-Aramaic nouns, and together they produce composite or periphrastic verbs.

The following verbs are those most common in the formation of such combinations, for example,

a) kardan ‘to do’:

- mahelo kardan ‘forgive’;

- misvo kardan ‘make circumcision’;

b) guftan ‘to say’:

mehelo guftan ‘ask forgiveness’ (on Yom Kippur ), barokho guftan ‘pray’, ‘bless’, lü guftan ‘object’, qadish guftan ‘say Kadish’ , qidusho guftan ‘say ceremonial blessing over wine’,

c) doshtan ‘to have’:

kavüd doshtan ‘be respected’ , zekhut doshtan ‘have merit, privilege’;

Many words, especially ones for household objects, are borrowed from Russian – such as istokon ‘cup’ (stakan); ishkof ‘closet’ (shkaf) and more (see Niazov, 1979). Some words are also borrowed from Yiddish, such as yorzeit (memorial) and shvarz (black). In addition, Judeo-Tajik includes a large number of words of Persian origin that never were or no longer are used in Tajik – such as oshi savo (the Sabbath meal), or archaic constructions such as arzoni shudan – to have the privilege of (immigrating to the land of Israel, for instance).

Most Bukharan Jews spoke at least two languages fluently. Jews living in Central Asia integrated words in Uzbek, Tajik, and other languages into their own language, while subjecting them to phonetic changes. So, for instance, certain Uzbek words replaced or were used alongside words in Judeo-Tajik: avr/kosh (eyebrows), or sar/kal (head). This phenomenon explains the type of synonymous repetition typical of Judeo-Tajik, which involves the simultaneous use of two synonyms, one of which is borrowed from another language – such as ushu (Tajik) hayol (Arabic) (‘thought’), or bakhtu (Tajik) mazol (Hebrew) (‘fate’).

Current status:

As of 2018, there are about 220,000 Bukharian Jews in the world, located in large communities in Israel and the USA, as well as in small communities in Austria, Germany, Canada, and Moscow; some families remain in Bukhara and Samarkand. About half of speakers are older than forty years old. Although there has not been an official estimate of language abilities, according to my observation 70% of them understand Judeo-Tajik, and 40% can speak.

There are some pages in periodicals in Judeo-Tajik: 1 page in “Menora” – a weekly newspaper of the World Bukharian Jewish Congress (Israel) – and 1 page in “Bukharian Times” – a weekly newspaper that is published in New York. There is a daily half-hour program in Judeo-Tajik on Israeli radio. There are some performances of amateur actors, as well as shows and concerts of professional musicians in Israel and NY.

In most Bukharan families today, children no longer speak Judeo-Tajik. Over the 120 years of Russian rule in Central Asia, most Bukharan Jews became Russian speakers. Today, the dominant language spoken by the young and intermediate generations of Bukharan Jews is the official language of their countries of residence. Judeo-Tajik is an endangered language.

Selected Bibliography

Aminüf, M.N. 1931. H,ajoti h,aqiqi. Tashkent: Uzbekskoe Gosudarstvennoe Izdatelstrvo.

Babaev, A. 1934. Osnovniye razlichiya mezhdu tuzemno-(bukh.)-yevreyskim i tadzhikskim yazikami. In Sbornik nauchnikh trudov. 2:67-74. Uz.NIIKS.

Babaev, K. 1991. Kommunikativnoye povedeniye yevreyev Bukhari. In Sovetskaya etnografiya.5:86-94. Moscow.

Birnbaum, S.A. 1950. The Verb in the Bukharic Language of Samarkand. In Archivum Linguisticum 2: 60. London.

Danielova (Tolmas), C. 1988. Gebraizmi v tadzhikskom dialekte sredneaziatskix yevreev. B Sinkhriniya i diakhroniya v lingvisticheskikh issledovaniyakh1: 95-100. Moscow.

Garkavi, A.Y. 1900. Persidsko-Yevreyskiy yazik. In Yevreyskaya Entziklopedia 12. 466. Sankt-Peterburg.

Gulkarov, J. 1998. Etymological Dictionary of Bukharan-Russian-English-Hebrew. Tel-Aviv.

Kalontarov, Y. 1934. Voprosy orfographii mestnoyevreyskogo yazika. In Problemy yazika. Sbornik uzbekskogo nauchno-issledovatelskogo instituta yazika i literatury, 1:53-60. Tashkent.

Kalontarov, Y. 1963. Sredneaziatskiye yevrei. In Narodi Srednei Azii i Kazakhstana II: 610-630. Moscow.

Kimyagarov A. and S. Niyazov. 1996. The Cuisine And Life Styles Of The Bokharian Jews. New-York.

Niyazov, D. 1979. O yazike sredneaziatskikh yevreyev. In Vonrosy vostokovedeniya. Yazikoznaniye. Sbornik Statey. 600:92-100. Tashkent.

Polivanov, E. 1989. K voprosy o proiskhozhdenii sredneaziatsko-yevreyskogo yazika. Samarkand.

Rastorgueva, V.S. 1963. Opit sravnitelnogo izucheniya tadzhikskikh govorov. 158. Moscow.

Rastorgueva, V.S. 1963. A Short Sketch of Tajik Grammar translated and edited by Herbert H. Paper. In International Journal of American Linguistics II, vol.29, N 4. Indiana University, Bloomington.

Schwarzwald, O.. 1985. The fusion of the Hebrew-Aramaic lexical component in Judeo-Spanish. In A Judeo-Romance Languages. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Misgav Yerushalayim: 139- 159.

Shalamaev, A. 1992. Fikrumolohizaho dar hususi zaboni mo – yaguduhoi bukhori. In Mas’al. 8:12-14. Tel-Aviv. El-hamayan.

Sukhareva, O. 1966. Bukhara XIX – XX vekov.165. Moscow. The Principles of the International Phonetic Association. London. 1972.

Tolmas, C. 2002. Anthroponymy of Bukharan Jews. Thesis, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Vaysenberg, S. 1912. Yevrei v Turkestane. In Yevreyskaya starina 4:392. Sankt-Peterburg.

Zand, M. 1979. Bimat hokrim. Habalshanut hayehudit-hameshutaf, hameyuhad vehabe’ayati. In Peamim 1:55.

Zand, M. 1991. Notes on the culture of the Non-Ashkenazi Jewish Communities Under Soviet Rule. In Jewish Culture and Identity in the Soviet Union. 378-444. New-York University Press.

Zand, M. 1998. Bukharan Jewish Culture of The Soviet Period: Its Formation, Evolvement and Destruction. In Stranitzi literaturi bukharskikh yevreev. 415-441. (Russian translation by Chana Tolmas). Tel-Aviv.

Zarubin, I. 1928. Ocherk razgovornogo yazika samarkandskikh yevreev. In IRAN-II. 91-181. Leningrad.

Online resources

Endangered Language Alliance Bukhori project:

Part of a comedy performance in Israel (in Judeo-Tajik and Hebrew, with some Russian)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HK0_h12r-js

Part of a comedy performance in New-York (in Judeo-Tajik and English, with some Russian)

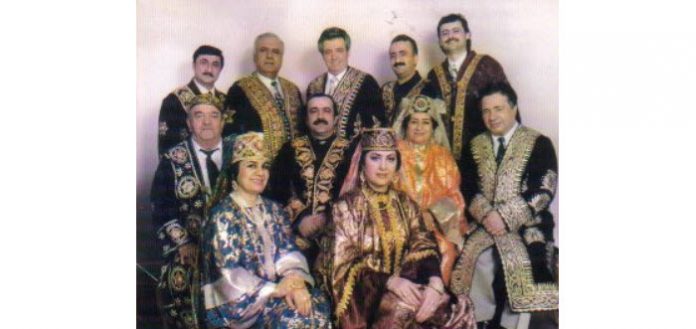

Part of a concert of the Bukharian Jewish Folk Ensemble “Maqom” in New York

credit to jewishlanguages.org