Israel’s capital has always been home to diverse Jewish communities.

One of Netflix’s most popular new shows is the Israeli import The Beauty Queen of Jerusalem. Based on Israeli author Sarit Yishai-Levi’s bestselling novel by the same name, the show stars Israeli heartthrob Michael Aloni, the star of Shtisel.

The story traces the fortunes of the Ermosa family, a Sephardi clan that has lived in Jerusalem for generations. Much of the drama comes from tensions between the “Espanola,” the Spanish Jewish community and other Jewish sects. The Beauty Queen of Jerusalem throws a spotlight onto the many diverse Jewish communities who’ve long called Jerusalem home.

In honor of Jerusalem Day, here is a roundup of a few of those colorful Jewish communities.

Medieval Jerusalemites

In the early Middle Ages, Jews living in Jerusalem maintained distinct customs and prayers. They were led by a sage known as a gaon (“a great one”), and the gaonim (plural for gaon) of this period traced their family lineages back to the Biblical leaders of Israel.

The glory of Medieval Jewish Jerusalem came to a horrific end when Crusaders attacked the city in 1099. Contemporary accounts describe how the Crusaders forced most of the city’s Jews into a synagogue and set it on fire, burning everyone alive. When the Medieval Jewish traveler Benjamin of Tudela visited Jerusalem in the year 1160, he found a much smaller, traumatized Jewish community living near the present-day Tower of David.

Jerusalem’s Medieval Jewish community slowly grew again, thanks in part to immigration from other lands. Historian Norman Roth notes that “many Jews immigrated to (the Land of Israel) throughout the Medieval period, including Jews from…Syria, Persia, Germany, and even Spain.” (Medieval Jewish Civilization, Norman Roth, ed. Routledge: 2003)

Entire communities of Jews often moved to Jerusalem along with their spiritual leaders. In 1211, a group of Jews from the French town of Sens relocated to Jerusalem, led by Rabbi Samson of Sens. One of the most famous Jewish sages to make Jerusalem his home during the Middle Ages was Rabbi Moses ben Nachman (also known as Ramban or Nachmanides). He moved to Jerusalem in the 1200s, and established the famous Ramban Synagogue, which still exists as a flourishing synagogue today.

Spanish Jews

Many of Jerusalem’s Jews during the late Middle Ages came from Spain, which was then the largest and most vibrant Jewish community in the world. Yet even in the midst of what’s sometimes called the “Golden Age” of Spanish Jewry, Spanish Jews continued to long for Israel, and for Jerusalem in particular.

The Medieval Spanish Jewish poet Yehuda Halevi put this longing into words in his poem “My Heart is in the East” in which he lamented that “It would be easy for me to leave behind all the good things of Spain: it would be glorious to see the dust of the ruined Temple” in Jerusalem. Yehuda Halevi did leave Spain and travel to Jerusalem, arriving after an arduous journey in 1141.

Many other Spanish Jews moved to Jerusalem, and in 1492 the trickle became a flood. That was the year that Spain’s King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella decreed that no Jew could remain living in Spain. Over a hundred thousand Jews fled the country, many settling in Jerusalem. One of the new arrivals was Rabbi Ovadiah of Bartenura (1445-1515), one of the leading rabbis of his generation, who established Jerusalem as a major center of Jewish scholarship once again.

At first, the new arrivals prayed in the Ramban Synagogue. In 1586, the local Ottoman governor appropriated the Ramban Synagogue, and Jerusalem’s Spanish Jewish community built their own house of worship, the Yochanan ben Zakkai Synagogue, which still functions today, serving Jerusalem’s Sephardi (“Spanish”) Jewish community.

“From now until the early 20th century, the streets of…Jerusalem would ring with the lyrical tones of their new Judaeo-Spanish language, Ladino,” the language of Spanish Jews, historian Simon Sebag Montefiore observes. (Jerusalem by Simon Sebag Montefiore, Alfred A. Knopf: 2011)

Bukharan Jews

Jews have lived in central Asia since ancient times. When the Mongol-Turkic military commander Tamerbek (1336-1405) established Samarkand as the capital of his Timurid Empire in 1370, he employed thousands of artisans in his cities. Many Jews moved to Samarkand and its environs, eventually adopting the local Persian language. These Jews were later called Bukharan, and formed an insular, intensely religious community, spanning present day Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan.

In about 1827 a Jewish traveler named David ben Hillel visited Samarkand. Little is known about his origins: he described himself only as “born in Europe, established in Safed near Jerusalem” and a devout Jew. He lived in the land of Israel, spending at least some of his time in Jerusalem, and traveled the world raising money for the new building projects of Jerusalem’s burgeoning Jewish community.

David ben Hillel’s presence in Samarkand and its environs electrified Bukharan Jews. Many decided to move to the holy city of Jerusalem, and began the difficult journey to the Land of Israel. The first Bukharan Jews reached Jerusalem in 1827. For decades, they sent word to their families and friends in central Asia, fueling yet more immigration. They maintained their own unique customs, even as they mixed with Jerusalem’s wider Jewish communities.

David ben Hillel’s presence in Samarkand and its environs electrified Bukharan Jews. Many decided to move to the holy city of Jerusalem, and began the difficult journey to the Land of Israel. The first Bukharan Jews reached Jerusalem in 1827. For decades, they sent word to their families and friends in central Asia, fueling yet more immigration. They maintained their own unique customs, even as they mixed with Jerusalem’s wider Jewish communities.

In the 1880s, as Jerusalem’s Jews began to build neighborhoods outside of Jerusalem’s Old City walls, Bukharan Jews bought property to the north of the city, near the present-day neighborhood of Meah Shearim. This Bukharan Quarter was home to dozens of modest homes. The synagogues were tiny – until one Bukharan Jew named Shlomo Moussaief (1852-1922) intervened. A wealthy merchant, Shlomo encouraged more Bukharan Jews to move to Jerusalem, and opened his own family home to house recent arrivals.

He built a grand synagogue in the Bukharan Quarter. Known as the Moussaieff Synagogue, it contained a Jewish ritual bath, a Turkish-style bath house, a museum (housing hand-written manuscripts by Jewish sages including Maimonides) and housing for poor Bukharan Jews. For years, the Moussaieff Synagogue employed poor Jewish scholars to write religious texts, helping to support Bukharan religious life in the city.

He built a grand synagogue in the Bukharan Quarter. Known as the Moussaieff Synagogue, it contained a Jewish ritual bath, a Turkish-style bath house, a museum (housing hand-written manuscripts by Jewish sages including Maimonides) and housing for poor Bukharan Jews. For years, the Moussaieff Synagogue employed poor Jewish scholars to write religious texts, helping to support Bukharan religious life in the city.

Thousands of Bukharan Jews moved to Jerusalem between the 1820s and the 1920s, but for many years the Soviet Union forbade Jewish emigration to Israel. After the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, over 5,000 more Bukharan Jews moved to Israel. Many settled in Jerusalem, but by then, the old Bukharan Quarter had changed. It’s no longer exclusively Bukharan – yet the area is still incredibly vibrant and the Moussaieff Synagogue continues to thrive today.

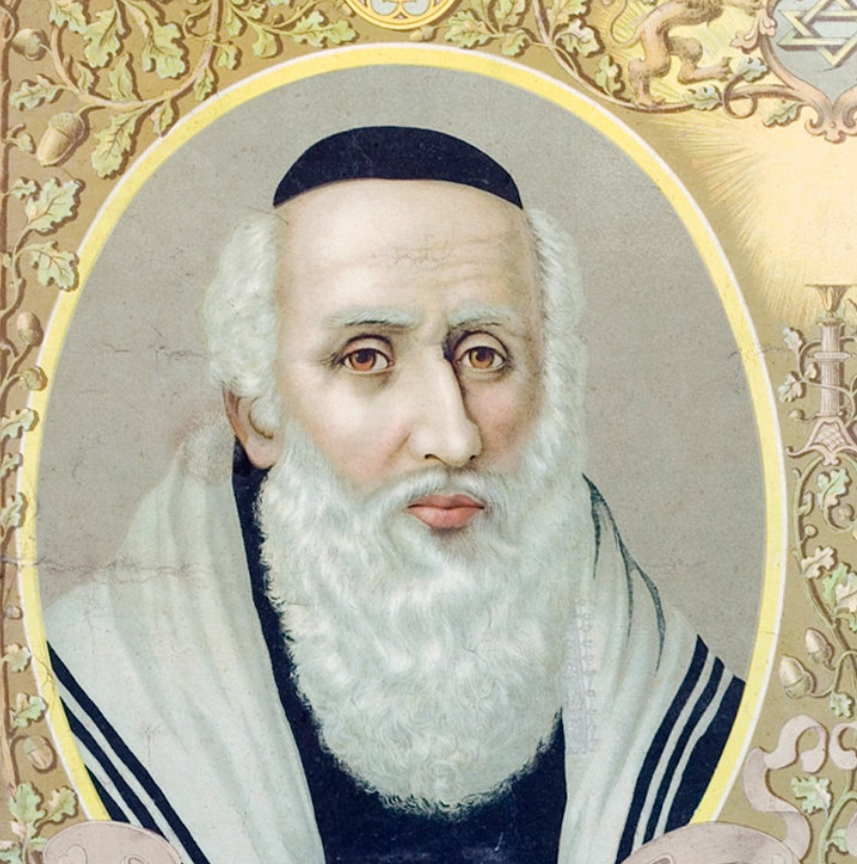

Lithuanian Jews – Students of the Vilna Gaon

Rabbi Elijah ben Solomon Zalman (1720-1797) was known as the Vilna Gaon – the “Great One” of Vilna, in Lithuania. A towering figure in European Jewry, he always wished to move to Jerusalem, but was unable to do so in his lifetime. His students, however, decided to make the Vilna Gaon’s dream a reality.

In 1809, 70 of his students traveled to Israel. The journey was difficult; they traveled overland in carriages to Istanbul, then sailed to the Israeli port of Acre. Eventually, over 500 of the Vilna Gaon’s students and their families made the long voyage. Denied permission to settle in Jerusalem by the Turkish authorities, this community moved first to the northern Israeli city of Safed. After an earthquake devastate Safed in 1837, this community of Jews finally succeeded in gaining permission to settle in Jerusalem. They hoped to lease land for agriculture, but for many years their pleas to become self-sufficient were met with denials from the local Muslim authorities.

New Jewish Neighborhoods

By the mid-1800s, the thousands of Jews who called Jerusalem home were horribly oppressed by their Turkish overlords, who ruled the Land of Israel. English writer W. E. Bartlett visited Jerusalem in 1853 and described the horrific situation of Jerusalem’s Jews:

There are approximately 7,000 Sephardim and 4,000 Ashkenazim. (Those who move to Jerusalem from Europe) usually bring small amounts of savings with them. It is a wretched life in a city where drinking water costs three to five pence for a donkey-load of four gallons…. Non-Muslims, if they wandered by mistake into the Temple compound, were beaten to the ground. (Jerusalem Revisited by W.E. Bartlett)

Help came from Sir Moses Montefiore, an Orthodox Jewish nobleman from Italy who’d moved to Britain and made a fortune in banking. Montefiore and his wife, Lady Judith Montefiore, traveled to Israel many times starting in the 1820s and they became fierce champions for the rights of Jews, both in the Land of Israel and all over the world.

A consummate diplomat, Sir Moses persuaded the Turkish authorities to close a garbage pit next to the Jewish Quarter in Jerusalem which routinely poisoned the groundwater and sickened Jerusalem’s Jews. In 1860, Sir Moses and Lady Judith funded a Jewish settlement outside of the Old City walls, freeing Jerusalem’s Jews from the tyranny and squalor of the cramped Jewish Quarter.

The settlement contained housing and even a windmill-powered grain mill so that Jews could mill their own flour and become self-sufficient. Many of the first settlers in the area were the Lithuanian followers of the Vilna Gaon.

The very first buildings that the Montefiores funded were a set of cottages for the poor called Mishkenot Shaanim (“Dwellings of Delight”). It was part of a wave of innovation that helped Jerusalem’s Jews venture out of the Old City of Jerusalem and start building the vibrant new neighborhoods that make Jerusalem so stunningly beautiful and lively today. Yemen Moshe still exists, as a popular neighborhood of Jerusalem filled with parks and upscale restaurants and galleries.

Yemenite Jews

Yemenite Jews began to arrive in Jerusalem in large numbers over a hundred years ago. An ancient and intensely religious community, the Jews of Yemen always nurtured hopes of returning to the Land of Israel. In the early 1800s, some brave Yemeni Jews began to make the arduous trek, walking from the southern tip of the Arabian Peninsula all the way to Jerusalem, a distance of about 1200 miles.

At the time, Yemeni authorities were increasing their persecution of Yemen’s Jews, particularly in the capital Sana; messages were arriving from Jerusalem describing the new building taking place their and some Yemeni Jews decided to be part of Jerusalem’s future.

Shalom Kassar and his father were some of the first Yemeni Jews to arrive in Jerusalem, in 1881. The journey had taken them six months. Dressed in old-fashioned Yemenite clothing and speaking the Yemenite Jews’ dialect of Arabic, they seemed foreign to Jerusalem’s Sephardi and Ashkenazi Jews. Shalom described their first encounter:

As dark fell, we arrived at the Jaffa Gate (of Jerusalem’s Old City)… At the time, they locked the gates at night. At long last, we arrived at the Jewish market. Since…we were wearing the clothing that we brought with us from Yemen, we looked different. The Jewish-Arabic language that we spoke was also strange to the people. The Jews from the Old City asked us: Who are you, and where did you come from? And we replied: We are Jews, and we came from the far away place Yemen.

They did not believe us, and they demanded that we show them some signs. We showed them a prayer book and tzitzit, we recited ‘Shema Yisrael’ – but they still did not believe us. In the end, they took my father into the Beit Midrash (study hall), opened a book of the Talmud, and asked him to read it. He read several lines fluently. Only then did they believe that we were really Jews… (When the Yemenite Pioneers Arrived in Jerusalem)

As more Yemeni Jews poured into Jerusalem, they built homes in Silwan, an ancient area adjacent to the Old City walls that is mentioned in the Talmud as a place where Jews used to joyously gather on the holiday of Sukkot in ancient times. There was already a Muslim village on the site: an 1870 Turkish census records 92 houses in the village. Starting in 1881, Yemenite Jews moved into Silwan; a 1891 record shows they’d built an additional 45 houses in the southern end of the village. Soon, Silwan was a major center of Yemenite Jewish life in the city. In 1948, during Israel’s War of Independence, Jordan seized the Silwan neighborhood, along with Jerusalem’s Old City, and forced all Jewish residents to leave. Yemenite Jews relocated to Israeli-held neighborhoods in the west of the city.

The center of the Jewish world for over 3,000 years, Jerusalem today is home to Jews from every corner of the world, each bringing their own beautiful traditions and customs with them, ensuring that every Jew, no matter where they come from, feels at home there.

credit aish.com