The ancient Silk Road city once had a thriving Jewish population, which has shrunk to around 200

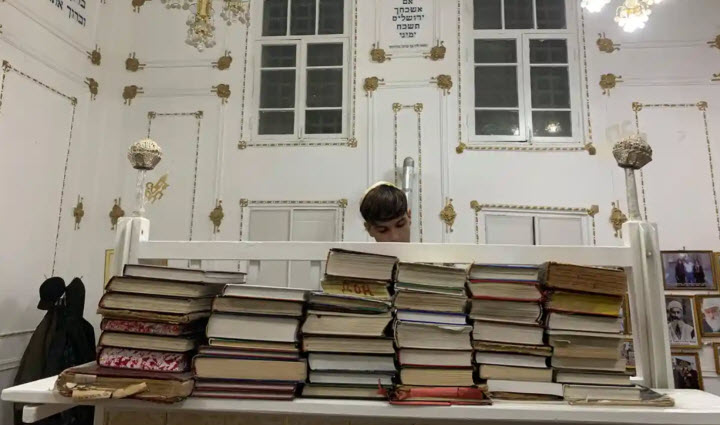

On the first night of Hanukah, Benyamin Badalov ascends the platformed bimah in Bukhara’s central synagogue to recite the evening prayer.

Among the handful of worshippers to attend, the tall 15-year-old, dressed in Nike trainers, sweats and an off-white yarmulke, is the youngest man in the room by decades.

“This is our future cantor,” says Abram Iskhakov, 70, the synagogue’s current cantor and the president of the Bukhara Jewish Community. “The youth don’t come, they go to Israel and America, but he comes.”

Once home to more than 23,000 Jews, the ancient Silk Road city of Bukhara now has around 200. Thousands of Bukharian Jews emigrated because of antisemitic policies under the Soviet Union, and still more due to Uzbekistan’s bleak economic prospects after its independence in 1991. The emigre community is far larger than its wellspring, with more than 50,000 Bukharian Jews in New York and more than 100,000 in Israel.

Despite boasting two synagogues, deep-pocketed foreign donors, and a Jewish school where Badalov learns Hebrew, the Jewish community in Bukhara has shrunk to the point where its future is in peril.

Those remaining are mostly elderly. Isak Gulyamov, 83, a retired geologist and father of five, fends off regular requests from his children to join them in Israel. All of his siblings have left, and three of his children have emigrated to Israel, and another to Kazakhstan.

He does not follow them because of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and because the humidity is bad for his blood pressure, he says, but mainly because Bukhara is home.

“It’s good for me here, I know everyone and everyone knows me,” he says during a short tour of the 420-year-old synagogue, set among the stone houses in Bukhara’s old Jewish quarter. Congregants take particular pride in a pair of centuries-old deerskin Torah scrolls, kept in a windowed cupboard beside gold-embroidered hangings.

But there is also little hope of seeing a generation of Bukharian Jews lost to emigration come back. “They’ve already put down roots, they’ve got a house, work. They’ve gotten used to it there, why come back?” says Gulyamov.

Congregants have tried to remain upbeat, saying that an improved economy and relaxed border controls could help bring more Jews back to the city, at least as tourists.

“It is like God said, propagate and multiply,” laughs Shirin Yakubova, a real-estate investor and descendant of the synagogue’s founder who is pregnant with her fourth child. “I have plenty of friends who want to invest in Bukhara now. Why shouldn’t more Jews want to come back? Half the year here, half the year in Israel.”

Despite its dwindling flock, the synagogue is well-connected. A picture on display shows that Hillary Clinton and Christine Lagarde have both visited, as well as the wife of the current president of Uzbekistan, and the French actor Gérard Depardieu.

“Watch, I’m going to talk to the mayor in front of you,” says Iskhakov as he looks at his rolodex and dials a number on speakerphone. When a voice answers in Uzbek, Iskhakov invites it to a Hanukah luncheon the following day (the mayor, regretfully, is on his way to Beijing, but a deputy will supposedly attend).

The Bukharian Jewish community has enjoyed a close relationship with the government in Uzbekistan. While the previous authoritarian leader Islam Karimov brutally targeted Islamists and isolated the country from the outside world, he largely left the Bukharian Jewish community in peace. The new president has experimented with limited reforms, for instance by easing travel in and out of the country, while maintaining total political power.

Ishakhov peppers his remarks with praise for the government, acknowledging the dwindling numbers of Jews in the city by saying that those who remain have never had it so good.

“They don’t even recognise their own streets, they’ve changed so much,” he says of Bukharian Jewish emigres when they visit the city. “They say: ‘If it had been like this before, we’d never have left.’” Indeed, the back streets of the Jewish quarter are a maze of building projects these days, signs of how economic changes could transform, but also upend, a centuries-old social fabric.

In the courtyard of the synagogue, Sofi Asadov and his wife, Delfuza, prepare a Bukharian Jewish delicacy – thick cuts of carp from Bukhara’s market marinated in coriander, garlic, and salt, then fried, refrigerated, and served on a bed of jellied kholodets.

The Asadovs are Muslim, as is the caretaker of the synagogue and the Jewish cemetery. He and his wife have occasionally cooked using kosher recipes for the synagogue since the former chef died and was not replaced. The synagogue’s elderly rabbi also died recently, and Iskhakov has been standing in for him since.

At the local Jewish cemetery, the caretaker says that since 1997, the number of people buried has jumped from 9,000 plots to more than 20,000. Flush with cash from donors and tourists, the synagogue has undergone a renovation of the cemetery worth hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Still, the dream is for new congregants than cash. Grigory, another retiree, can recall when Jews under 20 years old were barred from attending the synagogue and the crowds for Shabbat prayers spilled out of the synagogue and into the courtyard.

When asked about wedding planners and matchmakers to propagate a new generation of Bukharian Jews, he laughs: “We have not needed that for a long time.”

credit to theguardian.com